avia.wikisort.org - Aeroplane

The Airbus A400M Atlas[nb 2] is a European four-engine turboprop military transport aircraft. It was designed by Airbus Military (now Airbus Defence and Space) as a tactical airlifter with strategic capabilities to replace older transport aircraft, such as the Transall C-160 and the Lockheed C-130 Hercules.[3] The A400M is sized between the C-130 and the Boeing C-17 Globemaster III; it can carry heavier loads than the C-130 and is able to use rough landing strips. In addition to its transport capabilities, the A400M can perform aerial refueling and medical evacuation when fitted with appropriate equipment.

| A400M Atlas | |

|---|---|

| |

| A German Air Force A400M in flight | |

| Role | Strategic/tactical airlift / Aerial refueling |

| Manufacturer | Airbus Military / Airbus Defence and Space |

| First flight | 11 December 2009[1] |

| Introduction | 2013 |

| Status | In service |

| Primary users | German Air Force French Air and Space Force Spanish Air and Space Force Royal Air Force See Operators below for others |

| Produced | 2007–present |

| Number built | 111 as of 31 January 2022[nb 1][2] |

The A400M's maiden flight, originally planned for 2008, took place on 11 December 2009 from Seville Airport, Spain. Between 2009 and 2010, the A400M faced cancellation as a result of development programme delays and cost overruns; however, the customer nations chose to maintain their support for the project. A total of 174 A400M aircraft had been ordered by eight nations by July 2011. In March 2013, the A400M received European Aviation Safety Agency (EASA) certification. The first aircraft was delivered to the French Air Force in August 2013.

Development

Origins

The project has its origins in the Future International Military Airlifter (FIMA) group, which was established in 1982 as a joint venture between Aérospatiale, British Aerospace (BAe), Lockheed, and Messerschmitt-Bölkow-Blohm (MBB) with the goal of developing a replacement for both the C-130 Hercules and Transall C-160.[4] Varying requirements and the complications of international politics meant that progress on the initiative was slow. In 1989, Lockheed decided to withdraw from the grouping; it went on to independently develop an upgraded Hercules, the C-130J Super Hercules. With the addition of Alenia of Italy and CASA of Spain, the FIMA group became Euroflag.

Project management evaluated twin and quad turbofan engine configurations, a quad propfan configuration, and a quad turboprop configuration, eventually settling on the turboprop option.[5] Since no existing turboprop engine in the western world was powerful enough to reach the projected cruise speed of Mach 0.72, a new engine design was required. Originally, the SNECMA M138 turboprop (based on the M88 turbofan core) was selected, but this powerplant was found to be incapable of satisfying the requirements.[6][7] During April 2002, Airbus Military issued a new request for proposal (RFP), which Pratt & Whitney Canada with the PW180 and Europrop International answered. In May 2003, Airbus Military selected the Europrop TP400-D6. United Technologies alleged that the selection was a result of political interference.[8][9] A Europrop partner executive said on 16 April that Airbus was close to selecting the P&WC offer, claiming it was more than €400 million (US$436.7 million) cheaper than Europrop's bid.[10] Then as the original deadline for the engine decision passed, Airbus CEO Noel Forgeard said P&WC's bid was nearly 20 percent less expensive and declared that "As of today Pratt and Whitney is the winner without doubt, a much lower offer could make us change our minds." inviting Europrop to revise its offering, which it reportedly reduced in price by 10 or 20 percent.[11] A later report described the revised bid as exceeding P&WC's bid by €120 million.[12]

The original partner nations were France, Germany, Italy, Spain, the United Kingdom, Turkey, Belgium, and Luxembourg. These nations decided to charge the Organisation for Joint Armament Cooperation (OCCAR) with the management of the acquisition of the A400M. Following the withdrawal of Italy and revision of procurement totals, the revised requirement was for 180 aircraft. The first flight was forecast to occur during 2008 and the first delivery was to be in 2009. On 28 April 2005, South Africa joined the programme with the Denel Saab Aerostructures receiving a contract for fuselage components.[13] Malaysia is the second country outside Europe to be involved. Malaysia through CTRM is responsible for manufacturing composite aero components for the aircraft.[14]

The A400M is positioned as an intermediate size and range between the Lockheed C-130 and the Boeing C-17, carrying cargo too large or too heavy for the C-130 while able to use rough landing strips.[15]

Delays and problems

On 9 January 2009, EADS announced that the first delivery was postponed from 2009 until at least 2012, and indicated that it wanted to renegotiate.[16] EADS maintained the first deliveries would begin three years after the first flight. In January 2009, Financial Times Deutschland reported that the A400M was overweight by 12 tons and may not meet a key performance requirement, the ability to airlift 32 tons; sources told FTD that it could only lift 29 tons, insufficient to carry an infantry fighting vehicle like the Puma.[17] In response to the report, the chief of the German Air Force stated: "That is a disastrous development," and could delay deliveries to the German Air Force (Luftwaffe) until 2014.[18] The Initial Operational Capability (IOC) for the Luftwaffe was later delayed and alternatives, such as a higher integration of European airlift capabilities, were studied.[19]

On 29 March 2009, Airbus CEO Tom Enders told Der Spiegel that the programme may be abandoned without changes.[20] OCCAR reminded participating countries that they could terminate the contract before 31 March 2009.[21] In April 2009, the South African Air Force announced that it was considering alternatives to the A400M due to delays and increased cost.[22] On 5 November 2009, South Africa announced the order's cancellation.[23] On 12 June, The New York Times reported that Germany and France had delayed a decision whether to cancel their orders for six months while the UK planned to decide in late June. The NYT also quoted a report to the French Senate from February 2009, noting: "the A400M is €5 billion over budget, 3 to 4 years behind schedule, [and] aerospace experts estimate it is also costing Airbus between €1 billion and €1.5 billion a year."[24]

In 2009, Airbus acknowledged that the programme was expected to lose at least €2.4 billion and could not break even without export sales.[8] A PricewaterhouseCoopers audit projected that it would run €11.2 billion over budget, and that corrective measures would result in an overrun of €7.6 billion.[25] On 24 July 2009, the seven European nations announced that the programme would proceed and formed a joint procurement agency to renegotiate the contract.[26] On 9 December 2009, the Financial Times reported that Airbus requested an additional €5 billion subsidy.[27] On 5 January 2010, Airbus repeated that the A400M may be scrapped, costing it €5.7 billion unless €5.3 billion was added by partner governments,[28] delays had already increased its budget by 25%.[29] Airbus executives reportedly regarded the A400M as competing for resources with the A380 and A350 XWB programmes.[30]

In June 2009, Lockheed Martin said that both the UK and France had requested details on the C-130J as an alternative to the A400M.[31] In 2011, the ADS Group warned that shifting British orders to American aircraft for short term savings would cost more in missed business, stating that A400M technologies would be a bridge to a new generation of civil aircraft.[32]

On 5 November 2010, Belgium, Britain, France, Germany, Luxembourg, Spain and Turkey finalised the contract and agreed to lend Airbus Military €1.5 billion. The programme was then at least three years behind schedule. The UK reduced its order from 25 to 22 aircraft and Germany from 60 to 53, decreasing the total order from 180 to 170.[33]

In 2013, France's budget for 50 aircraft was €8.9bn (~US$11.7bn) at a unit cost of €152.4m (~US$200m), or €178m (~US$235m) including development costs.[34] The 2013 French White Paper on Defence and National Security cut the tactical transport aircraft requirement from 70 to 50.[35] As the A400M was unable to perform helicopter in-flight refuelling, France announced in 2016 that it would purchase four C-130Js.[36] In July 2016, French aerospace laboratory ONERA confirmed successful wind tunnel trials of a 36.5 m (120 ft) hose and drogue configuration that permits helicopter refuelling. Prior tests found instability in the intended 24 m (80 ft) hose due to vortices generated by the spoilers (deployed to achieve 108-130 kt air speed).[37]

On 1 April 2016, ADS stated it was addressing production faults affecting 14 propeller gearboxes (PGBs) produced by Italian supplier Avio Aero in early 2015. The issue, involving a heat treatment process that weakened the ring gear, affected no other PGBs; the units involved needed changing. Airbus noted: "pending full replacement of the batch, any aircraft can continue to fly with no more than one affected propeller gearbox installed and is subject to continuing inspections." Another PGB issue involved input pinion plug cracking, which could release small metallic particles into the oil system, which is safeguarded by a magnetic sensor; only engines 1 and 3, which have propellers that rotate to the right, are affected. The European Aviation Safety Agency (EASA) issued an Airworthiness Directive mandating immediate on-wing inspection, followed by replacement if evidence of damage is found.[38] On 27 April 2016, Airbus warned there may be a substantial PGB repair cost.[39] An interim PGB fix was certified in July 2016, greatly extending inspection intervals.[40]

In May 2016, Airbus confirmed that a cracking behaviour identified during quality control checks in 2011 was found in a French A400M's fuselage part; not affecting safety, it could be repaired during regular maintenance/upgrade schedules.[41][42] The aluminium-zinc alloy, known as 7000 series, was used in several central frames; its chemistry, along with environmental conditions, led to crack propagation. The alloy was excluded from future aircraft; a retrofit to remove it from early A400Ms was considered, which could take up to seven months.[43][44][45]

On 29 May 2016, Enders conceded in an interview published in Bild am Sonntag that some of the "massive problems" of the A400M were of Airbus' own making: "We underestimated the engine problems...Airbus had let itself be persuaded by some well-known European leaders into using an engine made by an inexperienced consortium." Furthermore, it had assumed full responsibility for the engine.[46] On 27 July 2016, Airbus confirmed that it took a $1 billion charge over delivery issues and export prospects.[47] Enders stated: "Industrial efficiency and the step-wise introduction of the A400M's military functionalities are still lagging behind schedule and remain challenging."[48]

Flight testing

Before the first flight, required airborne test time on the Europrop TP400 engine was gained using a C-130 testbed aircraft, which first flew on 17 December 2008.[49] On 11 December 2009, the A400M's maiden flight was carried out from Seville.[1] On 8 April 2010, the second A400M made its first flight.[50] In July 2010, the third A400M took to the air, at which point the fleet had flown 400 hours over more than 100 flights.[51] In July 2010, the A400M passed ultimate-load testing of the wing.[52] On 28 October 2010, Airbus announced the start of refuelling and air-drop tests.[53] By October 2010, the A400M had flown 672 hours of the 2,700 hours expected to reach certification.[54] In November 2010, the first paratroop jumps were performed; Enders and A400M project manager Bruno Delannoy were among the skydivers.[55]

In late 2010, simulated icing tests were performed on the MSN1 flight test aircraft using devices installed on the wing's leading edges. These revealed an aerodynamic issue causing horizontal tail buffeting, resolved via a six-week retrofit to install anti-icing equipment fed with bleed air; production aircraft are similarly fitted.[56] Winter tests were done in Kiruna, Sweden during February 2011.[57] In March 2012, high altitude start and landing tests were performed at La Paz at 4,061.5 m (13,325 ft) and Cochabamba at 2,548 m (8,360 feet) in Bolivia.[58][59]

By April 2011, a total of 1,400 flight hours over 450 flights had been achieved.[60] In May 2011, the TP400-D6 engine received certification from the EASA.[61] In May 2011, the A400M fleet had totaled 1,600 hours over 500 flights; by September 2011, the total increased to 2,100 hours and 684 flights.[62] Due to a gearbox problem, an A400M was shown on static display instead of a flight demonstration at the 2011 Paris Air Show.[63] By October 2011, the total flight hours had reached 2,380 over 784 flights.[56]

In May 2012, the MSN2 flight test aircraft was due to spend a week conducting unpaved runway trials on a grass strip at Cottbus-Drewitz Airport in Germany.[64] Testing was cut short on 23 May, when, during a rejected takeoff test, the left side main wheels broke through the runway surface. Airbus Military stated that it found the aircraft's behaviour was "excellent". The undamaged aircraft returned to Toulouse.[64]

At Royal International Air Tattoo 2012 the aircraft was officially named "Atlas"[65][66]

On 14 March 2013, the A400M was granted type certification by the EASA, clearing its entry to service.[67]

Production and delivery

Assembly of the first A400M began at the Seville plant of EADS Spain in early 2007. Major assemblies built at other facilities abroad were brought to the Seville facility by Airbus Beluga transporters. In February 2008, four Europrop TP400-D6 flight test engines were delivered for the first A400M.[68] Static structural testing of a test airframe began on 12 March 2008 in Spain.[69] By 2010, Airbus planned to manufacture 30 aircraft per year.[70] The Turkish partner, Turkish Aerospace Industries, delivered the first A400M component to Bremen in 2007.[71]

The first flight, originally scheduled for early 2008, was postponed due to delays and financial pressures. EADS announced in January 2008 that engine issues had been responsible for the delay. The rescheduled first flight, set for July 2008, was again postponed. Civil certification under EASA CS-25 shall be followed by certification for military uses. On 26 June 2008, the A400M was rolled out in Seville at an event presided by King Juan Carlos I of Spain.[72]

On 12 January 2011, serial production formally commenced.[73] On 1 August 2013, the first A400M was delivered to the French Air Force, it was formally handed over during a ceremony on 30 September 2013.[74][75] On 9 August 2013, the first Turkish A400M conducted its maiden flight from Seville;[76] in March 2015, Malaysia received its first A400M.[77]

In May 2015, it was revealed that the member nations had created a Programme Monitoring Team (PMT) to review and monitor progress in the A400M's development and production. The PMT inspects the final assembly line in Seville and other production sites. Early conclusions observed that Airbus lacked an integrated approach to production, development and retrofits, treating these as separate programmes.[78]

On 9 May 2015, an A400M crashed in Seville on its first test flight.[79] Germany, Malaysia, Turkey and UK suspended flights during the investigation.[80] Initial focus was on whether the crash was caused by new fuel supply management software for trimming the fuel tanks to enable certain manoeuvres; Airbus issued an update instructing operators to inspect all Engine Control Units (ECUs).[81] A key scenario examined by investigators is that the torque calibration parameter data was accidentally wiped on three engines during software installation, preventing FADEC operations.[82] On 3 June 2015, Airbus announced that investigators had confirmed "that engines one, two and three experienced power frozen after lift-off and did not respond to the crew's attempts to control the power setting in the normal way."[83]

On 11 June 2015, Spain's Ministry of Defence announced that prototypes could restart test flights and that further permits could be granted soon.[84] The RAF lifted its suspension on A400M flights on 16 June 2015, followed the next day by the Turkish Air Force.[85] On 19 June 2015, deliveries restarted.[86] In June 2016, the French Air Force accepted its ninth A400M, the first capable of conducting tactical tasks such as airdropping supplies. The revised standard includes the addition of cockpit armour and defensive aids system equipment, plus clearance to transfer and receive fuel in-flight.[87]

Design

The Airbus A400M increases the airlift capacity and range compared with the aircraft it was originally set to replace, the older versions of the Hercules and Transall. Cargo capacity is expected to double over existing aircraft, both in payload and volume, and range is increased substantially as well. The cargo box is 17.71 m (58.1 ft) long excluding ramp, 4.00 m (13.12 ft) wide, and 3.85 m (12.6 ft) high (or 4.00 m (13.12 ft) aft of the wing).[88] The maximum payload of 37 metric tons (41 short tons) can be carried over 2,000 nmi (3,700 km; 2,300 mi).[89] The A400M operates in many configurations including cargo transport, troop transport, and medical evacuation. It is intended for use on short, soft landing strips and for long-range, cargo transport flights.[88] The A400M is large enough to carry six Land Rovers and trailers, or two light armored vehicles, or a dump truck and excavator, or a Patriot missile system, or a Puma or Cougar helicopter, or a truck and 25-ton trailer.[90]

It features a fly-by-wire flight control system with sidestick controllers and flight envelope protection. Like other Airbus aircraft, the A400M has a full glass cockpit. Most systems are loosely based on those of the A380, but modified for the military mission. The hydraulic system has dual 207 bar (3,000 psi) channels powering the primary and secondary flight-control actuators, landing gear, wheel brakes, cargo door and optional hose-and-drogue refuelling system. As with the A380, there is no third hydraulic system. Instead, there are two electrical systems; one is a set of dual-channel electrically powered hydraulic actuators, the other an array of electrically/hydraulically powered hybrid actuators. The dissimilar redundancy provides more protection against battle damage.[91]

More than 30 percent of the airplane's structure is made of composite materials. The 42.4 m (139 ft) span wing is primarily made of carbon fibre reinforced plastic components, including the wing spars, the 19 m (62 ft) long, 12–14 mm (0.47–0.55 in) thick wingskins, and other parts. The wing weighs about 6,500 kg (14,330 lb), and it can carry and lift up to 25,000 kg (55,116 lb) of fuel.[92] It has an aspect ratio of 8.1, a wide chord of 5.6 m (18 ft), and a sweep angle of 15 degrees at 25 percent mean aerodynamic chord.[93]

The A400M has a T-tail empennage. Its vertical stabilizer is 8.02 m (26.3 ft) tall, while the horizontal stabilizer spans 19.03 m (62.4 ft) with a sweep of 32.5 degrees.[93]

The Ratier-Figeac FH385 propellers turn counterclockwise and the FH386 clockwise.[94] The eight-bladed scimitar propellers are made from a woven composite material. It is powered by four Europrop TP400-D6 engines rated at 8,250 kW (11,000 hp) each.[88] The TP400-D6 engine is the most powerful turboprop engine in the West to enter operational use.[61]

The pair of propellers on each wing turn in opposite directions, with the tips of the propellers advancing from above towards the midpoint between the two engines. This is in contrast to the overwhelming majority of multi-engine propeller driven aircraft where all propellers turn in the same direction. The counter-rotation is achieved by the use of a gearbox fitted to two of the engines, and only the propeller turns in the opposite direction; all four engines are identical and turn in the same direction. This eliminates the need to have two different "handed" engines on stock for the same aircraft, simplifying maintenance and supply costs; this configuration, dubbed down between engines (DBE), allows it to produce more lift and lessens the torque and prop wash on each wing. It also reduces yaw in the event of an outboard engine failure.[95] Due to these benefits, the vertical stabilizer can be reduced by 17 percent in size, while the size of the horizontal stabilizer can be shrunk by 8 percent.[93]

A forward-looking infrared enhanced vision system (EVS) camera provides an enhanced terrain view in low-visibility conditions. The EVS imagery is displayed on the HUD for low altitude flying, demonstrating its value for flying tactical missions at night or in cloud.[91] EADS and Thales provides the new Multi-Colour Infrared Alerting Sensor (MIRAS) missile warning sensor for the A400M.[96][97]

The A400M has a removable refuelling probe mounted above the cockpit, allowing it to receive fuel from drogue-equipped tankers.[88] Optionally, the receiving probe can be replaced with a fuselage-mounted UARRSI receptacle for receiving fuel from boom equipped tankers.[98] It can also act as a tanker when fitted with two wing mounted hose and drogue under-wing refuelling pods or a centre-line Hose and Drum unit.[88] The refuelling pods can transfer fuel to other aircraft at a rate of 2,640 lb/min (20.0 kg/s).[90]

The A400M features deployable baffles in front of the rear side doors, intended to give paratroops time to get clear of the aircraft before they are hit by the slipstream.[99]

Operational history

On 29 December 2013, the French Air Force performed the A400M's first operational mission: an aircraft flew to Mali in support of Operation Serval.[100]

On 10 September 2015, the RAF was declared the A400M fleet leader in terms of flying hours, with 900 hours flown over 300 sorties, achieved by a fleet of four aircraft. Sqn. Ldr. Glen Willcox of the RAF's Heavy Aircraft Test Squadron confirmed that reliability levels were high for an aircraft so early in its career, and that night vision goggle trials, hot and cold soaking, noise characterization tests and the first tie-down schemes for cargo had already been completed. In March 2015, the RAF's first operational mission occurred, flying cargo to RAF Akrotiri, Cyprus.[101]

In September and October 2017, A400Ms from France, Germany and the UK participated in the disaster relief operations following Hurricane Irma in the Caribbean, delivering a Puma helicopter, food, water and other aid supply, and evacuating stranded people.[102][103]

On 24 July 2018, the German Luftwaffe used an A400M in combat conditions for the first time, transporting 75 soldiers from Wunstorf to Mazar-i-Sharif.[104] German Air Force Inspector Ingo Gerhartz called this a "milestone" because it was the first such mission in an active war zone and showed that the armoring kit was fully functional.[105]

On 7 September 2018, the French Air and Space Force announced that they had logged 10,000 flying hours with their fleet of 14 A400Ms, mostly flying supply missions for Operation Barkhane.[106]

The German government had planned to sell the last 13 A400Ms out of its order of 53 aircraft but failed to attract any buyers. Instead, the government decided to employ them in service. During a visit to the Wunstorf Air Base on 2 January 2019, the German Minister of Defence Ursula von der Leyen announced that the 13 A400Ms will be used to form a multinational airlift wing. Due to a lack of space at Wunstorf and for greater flexibility, the future air wing will be based at Lechfeld Air Base in southern Germany.[107]

In 2019, a German A400M in tanker configuration replaced the Airbus A310 MRTT deployed to Muwaffaq Salti Air Base in Jordan to refuel allied aircraft as part of the German intervention against ISIL.[108]

In August 2021, a total of 25 A400Ms were deployed by Belgium, France, Germany, Spain, Turkey and the UK to assist in the Kabul Airport evacuations.[109][110][111][112] German A400Ms evacuated 5347 people over the course of 35 flights.[113]

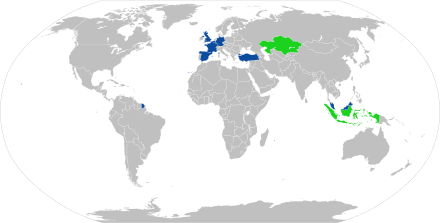

Exports

- Chile

In July 2005, the Chilean Air Force signed a Memorandum of understanding for three aircraft,[114] but no order was placed; Chile began talks on buying the Brazilian Embraer KC-390.[115]

- Czech Republic

In February 2017, the Czech Ministries of Defence stated they were interested in a joint lease of A400Ms from Germany.[116]

- Hungary

In September 2020, Hungary was named as the first partner of the Multinational Air Transport Unit to be established at Lechfeld Air Base with 10 A400Ms contracted to Germany.[117]

- Indonesia

In January 2017, Indonesia approved the acquisition of five A400Ms to boost the country's military airlift capabilities.[118] In March 2017, a letter of intent with Airbus was signed by Pelita Air Services, representing a consortium of Indonesian aviation companies.[119] In March 2018, the Indonesian Air Force and state entity Indonesia Trading Company (ITC) announced they were considering ordering two A400Ms, which would be crewed by the Indonesian Air Force and act in an air freight role helping to balance the prices of goods across the archipelago. The parties were interested in the aircraft's ability to operate from rough landing strips, where a normal air freighter could not, as well as the possibility of industrial offsets.[120] In November 2021, Airbus confirmed that the Indonesian Ministry of Defense had signed a deal with Airbus for two A400Ms, with an option, in the form of a letter of intent, for four additional aircraft.[121]

- Kazakhstan

In September 2021, Kazakhstan signed an agreement with Airbus to buy two A400Ms for the Kazakhstan Air Force.[122]

- Malaysia

In December 2005, the Royal Malaysian Air Force ordered four A400Ms to supplement its fleet of C-130 Hercules.[123]

- South Africa

In December 2004, South Africa announced it would purchase eight A400Ms at a cost of approximately €837 million, with the nation joining the Airbus Military team as an industrial partner. Deliveries were expected from 2010 to 2012.[124] In 2009, South Africa cancelled all eight aircraft, citing increasing costs. On 29 November 2011, Airbus Military reached an agreement to refund pre-delivery payments worth €837 million to Armscor.[125]

- South Korea

In February 2019, South Korea's Defense Acquisition Program Administration (DAPA) confirmed a proposal from Spain to swap an undetermined number of KAI T-50 Golden Eagles and KAI KT-1 Woongbi trainers for A400M airlifters.[126]

Variants

- A400M Grizzly

- Five prototype and development aircraft, a sixth aircraft was cancelled.

- A400M-180 Atlas

- Production variant

Operators

| Date | Country | Orders | Deliveries | Entry into service date |

Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 27 May 2003 | 53 | 37[2] | December 2014[127] | Order reduced from 60 to 53 (plus 7 options),[128] and will integrate 10 into an international transport alliance.[117] | |

| 50 | 19[2] | August 2013[129] | |||

| 27 | 13[2] | November 2016[130] | Original budget of €3,453M increased to €5,493M in 2010.[131] Delivery of 13 aircraft has been delayed until 2025–2030.[132] | ||

| 22 | 21[133] | November 2014[134] | Order reduced from 25 to "at least 22".[135] A purchase of additional aircraft is planned for the late 2020s.[136] | ||

| 10 | 10[2] | April 2014[137] | Turkey completes its A400M fleet with 10th delivery.[138] | ||

| 7 | 6[2] | December 2020[139] | |||

| 1[2] | 1[140] | October 2020[140] | Stationed in Belgium as a part of a bi-national fleet.[141] | ||

| 8 December 2005 | 4 | 4[2] | March 2015[142] | First non-NATO country to purchase the A400M. Final A400M delivered in March 2017.[142] | |

| 1 September 2021 | 2[122] | 0 | Expected 2024[122] | Deliveries scheduled from 2024.[122] | |

| 18 November 2021 | 2 (4 options) | 0 | Unknown | Two A400Ms in MRTT configuration were ordered to boost the country's military airlift and aerial refueling capabilities; a letter of intent contains options for four additional aircraft.[121] | |

| Total: | 178[2] | 110[2] |

Accidents

An A400M crashed on 9 May 2015, when aircraft MSN23, on its first test flight crashed shortly after take-off from San Pablo Airport in Seville, Spain, killing four Spanish Airbus crew and seriously injuring two others. Once airborne, the crew contacted air traffic controllers just before the crash about a technical failure,[143] before colliding with an electricity pylon while attempting an emergency landing.[144] The crash was attributed to the FADEC system being unable to read engine sensors properly due to an accidental file-wipe, resulting in three of its four propeller engines remaining in "Idle" mode during takeoff.[145]

Specifications

Data from Airbus Defence & Space specifications[146][147]

General characteristics

- Crew: 3 or 4 (2 pilots, 3rd optional, 1 loadmaster)

- Capacity: 37,000 kg (81,600 lb)

- Length: 45.1 m (148 ft 0 in)

- Wingspan: 42.4 m (139 ft 1 in)

- Height: 14.7 m (48 ft 3 in)

- Wing area: 225.1 m2 (2,384 sq ft)

- Empty weight: 78,600[148] kg (173,283 lb)

- Max takeoff weight: 141,000 kg (310,852 lb)

- Fuel capacity: 50,500 kg (111,300 lb) internal fuel

- Max landing weight: 123,000 kg (271,000 lb)

- Powerplant: 4 × Europrop TP400-D6 turboprop, 8,200 kW (11,000 hp) each

- Propellers: 8-bladed Ratier-Figeac variable pitch propellers with feathering and reversing capability[nb 3][94], 5.3 m (17 ft 5 in) diameter

Performance

- Maximum speed: Mach 0.72

- Cruise speed: 781 km/h (485 mph, 422 kn) at 9,450 m (31,000 ft)[91]

- Initial cruise altitude: 9,000 m (29,000 ft) at MTOW

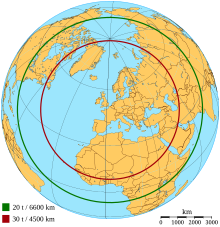

- Range: 3,300 km (2,100 mi, 1,800 nmi) at max payload[nb 4]

- Range with 30-tonne payload: 4,500 km (2,450 nmi)

- Range with 20-tonne payload: 6,400 km (3,450 nmi)

- Ferry range: 8,700 km (5,400 mi, 4,700 nmi)

- Service ceiling: 12,200 m (40,000 ft)

- Wing loading: 637 kg/m2 (130.4[91] lb/sq ft)

- Tactical takeoff distance: 980 m (3,215 ft)[nb 5]

- Tactical landing distance: 770 m (2,530 ft)[nb 5]

- Turning radius (ground): 28.6 m

See also

Aircraft of comparable role, configuration, and era

- Antonov An-70 – Ukrainian/Russian military transport aircraft prototype by Antonov

- Ilyushin Il-76 – Russian heavy military transport aircraft

- Kawasaki C-2 – Japanese military transport aircraft

- Embraer C-390 Millennium – Brazilian military transport aircraft/tanker

Notes

- Includes five prototype and development aircraft and one crashed before delivery.

- Named after the Greek mythological figure.

- FH385 anticlockwise on engines 2 and 4, FH386 clockwise on engines 1 and 3)

- long range cruise speed; reserves as per MIL-C-5011A)

- aircraft weight 100 tonnes (98 long tons; 110 short tons), soft field, ISA, sea level

References

- "Updated- Pictures & Video: Airbus celebrates as A400M gets airborne". Flight International. 11 December 2009. Archived from the original on 14 December 2009.

- "Orders, Deliveries, In Operation Military aircraft by Country - Worldwide" (PDF). Airbus. Retrieved 16 February 2022.

- RAF – A400m., MOD, archived from the original on 30 April 2009, retrieved 15 May 2010

- Hewson, R. The Vital Guide to Military Aircraft, 2nd ed. Airlife Press, Ltd. 2001.

- López Díez, J.L.; Asenjo Tornell, J.L. (3 October 2018). A400M aircraft: Design requirements & conceptual definition (PDF). Madrid, Spain. pp. 10–12.

- "Tracing the tangled roots" (PDF). Flight International. 9–15 November 2004. p. 59. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 November 2015.

- "Tracing the tangled roots" (PDF). Flight International. 9–15 November 2004. p. 60. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 November 2015..

- Michaels, Daniel (2 December 2009). "Airbus Transport Is Almost Ready for Takeoff". Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 18 October 2015.

- Lewis, Paul (13 May 2003). "USA blasts A400M engine choice". Flight International. Archived from the original on 18 May 2015. Retrieved 9 May 2015.

- Aguera, Martin (21 April 2003). "Non-European engine may power A400M". Defense News. Vol. 18, no. 16. Berlin, Germany. p. 1. ISSN 0884-139X – via NewsBank.

- "EADS backs European supplier for Airbus military plane". Paris, France. Agence France-Presse. 6 May 2003.

- Schwarz, Karl (July 2003). "A400M: Fewer aircraft - higher price". Flug Revue. p. 62. ISSN 0015-4547. Archived from the original on 25 June 2003.

- "South Africa to Cancel its A400M Order." Archived 20 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine Defense Industry Daily. Retrieved: 2 May 2012.

- "Products & Services (Aerospace)". Composites Technology Research Malaysia. Archived from the original on 13 July 2018. Retrieved 13 July 2018.

- Harvey, Dave (16 July 2010). "Will the world buy the A400M?". BBC News. Archived from the original on 16 October 2016. Retrieved 17 November 2016.

- Regan, James and Tim Hepher. EADS wants A400M contract change, adds delay>" Archived 18 October 2015 at the Wayback Machine Reuters, 9 January 2009. Retrieved: 1 July 2011.

- "Airbus A400M military transport reportedly too heavy and weak.' Archived 14 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine Thelocal.de. Retrieved: 20 July 2010.

- "Business: EADS denies mulling collapse of A400M project." Archived 29 November 2014 at the Wayback Machine Khaleejtimes.com, 23 January 2009.

- "Sascha Lange: The End for the Airbus A400M?" Archived 28 July 2009 at the Wayback Machine. SWP Comments, 26 February 2009.

- Evans-Pritchard, Ambrose. "Airbus admits it may scrap A400M military transport aircraft project." Archived 24 June 2018 at the Wayback Machine The Daily Telegraph, 29 March 2009.

- Airbus-Projekt A400M droht zu scheitern Archived 2 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine, Der Spiegel, 27 February 2009.

- Engelbrecht, Leon. "SAAF considering A400M alternative" Archived 19 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine. DefenceWeb, 3 April 2009.

- "Govt cancels multibillion-rand Airbus contract". mg.co.za. 5 November 2009. Archived from the original on 18 November 2016. Retrieved 17 November 2016.

- Brothers, Caroline. "Germany and France Delay Decision on Airbus Military Transport." Archived 30 March 2017 at the Wayback Machine The New York Times, 11 June 2009.

- "Factbox: The big money behind Airbus A400M talks." Archived 17 November 2015 at the Wayback Machine Reuters, 21 January 2010.

- "Airbus gets extension of A400M Contract Moratorium." Archived 17 November 2015 at the Wayback Machine Bloomberg News, 27 July 2009.

- "EADS pleads for €5bn to complete A400M". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 12 March 2010.

- Hollinger, Peggy, Pilita Clark and Jeremy Lemer. "Airbus threatens to scrap A400M aircraft." Archived 24 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine Financial Times, 5 January 2010.

- "Airbus chief 'may cancel A400M'." Archived 12 January 2010 at the Wayback Machine BBC News, 12 January 2010.

- "Airbus' military plane continues to distract". BBC News. 3 February 2010. Archived from the original on 16 April 2016. Retrieved 17 November 2016.

- "U.K., France Seek Data on Super Hercules Plane, Lockheed Says." Bloomberg.

- Pocock, Chris. "Fresh doubts over A400M as Europe tightens its belt." ainonline.com. Retrieved: 9 September 2011. Archived 21 July 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- Christina Mackenzie (1 January 2011). "Partner Nations Approve A400M Contract". Aviation Week. Archived from the original on 28 April 2016.

- "Projet de loi de finances pour 2014 : Défense : équipement des forces" (in French). Senate of France. 21 November 2013. Archived from the original on 13 January 2014.

- Merchet, Jean-Dominique (30 April 2013). "Armée de l'air : moins d'une quarantaine d'A400M devrait être commandée" (in French). Marianne. Archived from the original on 10 May 2013.

- Stevenson, Beth (5 January 2016). "France reportedly confirms C-130J buy". Flightglobal. Archived from the original on 28 March 2016.

- "French aerospace laboratory details A400M refuelling tests". FlightGlobal. 25 July 2016. Archived from the original on 26 July 2016.

- "Airbus A400M engine glitch seen taking weeks to fix". Reuters. 5 April 2016. Archived from the original on 23 June 2018.

- "Airbus Reports A400M Engine Gearbox Problems Will Cause Delays". Defense News. 28 April 2016. Archived from the original on 15 May 2016.

- Shalal, Andrea (9 July 2016). "Interim fix for A400M engine issue certified: Airbus". reuters.com. Reuters. Archived from the original on 12 July 2016.

- "Airbus wants to replace A400M parts after cracks found, Germany says". Reuters. 13 May 2016. Archived from the original on 12 September 2017.

- "Germany Presses Airbus to Resolve A400M Problems". Defense News. 18 May 2016.

- "Airbus Works Through A400M Woes". Aviation Week. 1 July 2016. Archived from the original on 2 July 2016.

- "A400M Technical Problems". www.globalsecurity.org. Retrieved 29 July 2022.

- Plokker, Matthijs; Daverschot, Derk; Beumler, Thomas (2009). Bos, M. J. (ed.). "Hybrid Structure Solution for the A400M Wing Attachment Frames". ICAF 2009, Bridging the Gap Between Theory and Operational Practice. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands: 375–385. doi:10.1007/978-90-481-2746-7_22. ISBN 978-90-481-2746-7.

- "Airbus Concedes Some A400M Problems Are 'Homemade'". Defense News. 29 May 2016. Archived from the original on 10 May 2017. Retrieved 31 May 2016.

- "Airbus Announces Additional €1B in Financial Charges for A400M". Defense News. 28 July 2016.

- "Airbus takes fresh €1bn charge against A400M". FlightGlobal. 27 July 2016. Archived from the original on 28 July 2016.

- Kaminski-Morrow, David (17 December 2008). "Airbus A400M's engine becomes airborne for first time". Flightglobal. Archived from the original on 18 December 2008.

- "Second Airbus Military A400M completes maiden flight" (Press release). Airbus Military. 9 April 2010. Archived from the original on 18 May 2015.

- Hoyle, Craig (9 July 2011), "Picture: Third A400M takes to the air.", Flight International, archived from the original on 11 July 2010

- "A400M wing passes critical test." defpro.com, 3 August 2010. Archived 17 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- "A400M close to first air drop, refuelling tests, says Airbus." Archived 31 October 2010 at the Wayback Machine Flightglobal.com, 31 October 2010.

- Kingsley-Jones, Max; Flottau, Jens (4 November 2010). "Airbus To Ramp Up A400M Test Effort". Aviation Week.

- Hoyle, Craig. "Picture: First paratroops jump from Europe's A400M." Archived 10 November 2010 at the Wayback Machine Flightglobal.com, 10 November 2010.

- Hoyle, Craig (27 October 2011). "Bearing up: Airbus Military's 'Grizzly' nears civil certification". Flight International. Archived from the original on 10 November 2011.

- Perry, Dominic. "A400M undergoes Swedish winter trials." Archived 11 February 2011 at the Wayback Machine Flight International, 8 February 2011.

- "The global tour of the A400M." Archived 29 November 2014 at the Wayback Machine Second Line of Defense. Retrieved: 16 April 2012.

- "A400M has high time in La Paz" Archived 30 July 2012 at the Wayback Machine Flightglobal, 30 March 2012.

- Hoyle, Craig. "A400M contract amendment signed, as test fleet passes 1,400 flight hours." Archived 10 April 2011 at the Wayback Machine Flight International, 7 April 2011.

- Chuter, Andrew. "A400M Engine Wins Safety Certification." Defense News, 6 May 2011.

- Hoyle, Craig. "Pictures: New-look A400M readied for icing trials." Flight International, 16 July 2011.

- Morrison, Murdo. "Paris: Engine problems prevent A400M flying at show." Archived 22 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine Flight International, 19 July 2011.

- Hoyle, Craig. "Soft ground cuts short A400M landing trials." Archived 7 June 2012 at the Wayback Machine Flightglobal, 25 May 2012.

- A400M naming ceremony at RIAT., Airbus Military, 6 July 2012, archived from the original on 17 December 2013

- Hoyle, Craig (6 July 2012), "RIAT: A400M reborn as 'Atlas'", Flightglobal, archived from the original on 17 December 2013.

- "Airbus Military A400M Receives Full Civil Type Certificate From EASA". defense-update.com. 14 March 2013. Archived from the original on 19 April 2015. Retrieved 9 May 2015.

- "Fourth Engine for A400M Brings First Flight Closer". Reuters,

- "Static test programme begins on aircraft MSN 5000". EADS, 28 March 2008. Archived 8 July 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- "A400M Countdown #4 – A Progress report from Airbus Military." Archived 16 July 2007 at the Wayback Machine A400m-countdown.com. Retrieved: 20 July 2010.

- "TAI Achieves Shipment of the First A400M Component to Bremen". www.defense-aerospace.com.

- "El Rey estrena el Airbus 400, el mayor avión militar de fabricación europea." Archived 20 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine ELPAÍS.com.

- "A400M Gets Going". 12 January 2011. Archived from the original on 2 October 2012.

- "French acceptance sees A400M deliveries take off" Archived 2 November 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Flight International, 1 August 2013.

- "France formally accepts A400M transport" Archived 19 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Flight International, 30 September 2013.

- "First Airbus Military A400M for Turkish Air Force makes maiden flight". EADS. 12 August 2013. Archived from the original on 29 October 2013.

- Waldron, Greg (10 March 2015). "Malaysia receives first A400M". Flightglobal. Archived from the original on 12 March 2015.

- "A400M Countries Form Monitoring Team, Germany Warns of Airlift Gap". Aviation Week. 21 May 2015. Archived from the original on 22 May 2015.

- M. J. Pereira (10 May 2015). "El A400M accidentado comunicó problemas en el tren de aterrizaje tras despegar". ABC de Sevilla. Archived from the original on 18 May 2015.

- "UK halts Airbus A400M usage after Seville crash". 10 May 2015. Archived from the original on 18 March 2017.

- "Software Cut Off Fuel Supply in Stricken A400M". Aviation Week. Archived from the original on 22 May 2015. Retrieved 19 May 2015.

- "A400M probe focuses on impact of accidental data wipe". Reuters. 9 June 2015. Archived from the original on 3 November 2015.

- "Airbus Says 3 of 4 Engines Failed in Spain A400M Crash". Defense News. 27 May 2015.

- "Airbus can restart A400M test flights in Spain after crash: Defense Ministry". Reuters. 11 June 2015. Archived from the original on 18 October 2015.

- "Airbus hoping to resume A400M deliveries". Financial Times. 17 June 2015. Archived from the original on 17 November 2015.

- "Airbus resumes A400M customer deliveries". IHS Jane's 360. 22 June 2015. Archived from the original on 24 June 2015.

- "France receives first A400M with tactical capability". FlightGlobal. 22 June 2016. Archived from the original on 23 June 2016.

- "Military Aircraft Airbus DS – A400M". Airbus Military. Archived from the original on 1 July 2014. Retrieved 9 May 2015.

- "ABOUT THE ATLAS (A400M)". RAF. Archived from the original on 6 April 2019.

- Mraz, Stephen J. (17 February 2005). "Airbus builds a military airlifter: A new, multirole transporter will replace aging heavy-lift aircraft in military fleets". Cover Story. Machine Design. Vol. 77, no. 4. pp. 98+. ISSN 0024-9114. Archived from the original on 24 June 2020.

- "Pilot Report Proves A400M's Capabilities". Aviation Week. 10 June 2013. Archived from the original on 18 October 2015.

- Sloan, Jeff (2013). "A400M wing assembly: Challenge of integrating composites". High Performance Composites. Vol. 21, no. 1. pp. 26–31. ISSN 1081-9223. OCLC 838365211.

- Norris, Guy (9–15 November 2004). "Under the skin: Airbus Military's airlifter has several things in common with its commercial siblings, sharing dimensions and composites technology that were pioneered for airliners". A400M: Airframe. Flight International. Vol. 166, no. 4959. Toulouse, France. pp. 46+. ISSN 0015-3710. Archived from the original on 2 July 2020.

- "EASA Type Certificate Data Sheet for A400M-180" (PDF). europa.eu. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 May 2018. Retrieved 9 May 2018.

- "Focus on innovation: Down-Between-Engines (DBE)". Airbus Military. Archived from the original on 1 May 2008.

- "IR Sensors Page 4 English Seite 5 deutsch. IAF.Fraunhofer Archived 31 July 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- "EADS and Thales to supply latest-technology missile warner to A400M". globalsecurity.org. Archived from the original on 7 January 2006.

- "A400M as a tanker" (PDF). Airbus Military. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 14 May 2013.

- Klimek, Chris (1 April 2015). "Tom Cruise Hangs on to a Flying Airbus (Really) in the Next Mission Impossible". airspacemag.com. Archived from the original on 10 May 2015.

- Hoyle, Craig (6 January 2014). "French Mali mission gives A400M operational debut". Flight International. Archived from the original on 13 February 2014.

- "A400M Deliveries Create Headaches For Uk". Aviation Week. 11 September 2015.

- Vigoureux, Thierry (10 September 2017). "Irma : l'Airbus A400M opérationnel aux Antilles" [Irma: Airbus A400M operative in the Antilles]. lepoint.fr (in French). Paris. Archived from the original on 29 July 2018.

- Gebauer, Matthias (11 September 2017). "Bundeswehr startet Rettungsmission in der Karibik" [Bundeswehr starts rescue mission in the Caribbean]. spiegel.de (in German). Hamburg. Archived from the original on 19 February 2018.

- "Lufttransportgeschwader 62: A400M der Luftwaffe fliegt erstmals nach Afghanistan". www.flugrevue.de. 25 July 2018.

- "Bundeswehr: Erstmals Bundeswehrsoldaten mit Problemflugzeug A400M nach Afghanistan gebracht". Die Welt. 25 July 2018 – via www.welt.de.

- "A400M der Armée de l'Air haben 10.000 Flugstunden erreicht". Aerobuzz.de. 7 September 2018.

- "Joy in Lechfeld - The A400M is coming". Official Luftwaffe website. 3 January 2019. Archived from the original on 4 January 2019.

- "The A400M will replace the A310 tanker already deployed in German Operation "Counter Daesh"". The Aviationist. 9 July 2019. Retrieved 13 December 2020.

- "New Airbus military aircraft chief bullish on A400M, MRTT prospects". FlightGlobal. 6 September 2021. Retrieved 10 January 2022.

- "Third French flight of evacuees from Kabul touches down in Paris". France 24. 19 August 2021. Retrieved 23 August 2021.

- Estebanez García, Diego; Chouza, Paula (17 August 2021). "First military plane due to repatriate Spanish nationals from Afghanistan takes off from Zaragoza". EL PAÍS. Retrieved 23 August 2021.

- Roblin, Sebastien. "823 People, One Jet: Flight Trackers Reveal Heroic, Desperate Effort In Chaotic Afghanistan Evacuation". Forbes. Retrieved 23 August 2021.

- "Letzte A400M haben Kabul verlassen: Afghanistan-Rettungsaktion beendet". 27 August 2021.

- Airbus Military signs agreement with Chile Airbus Military. Archived 6 April 2005 at the Wayback Machine

- Roberts, Janice (19 December 2011). "Airbus refunds A400M payments to Armscor". MoneyWeb South Africa. Johannesburg. Archived from the original on 21 February 2017.

- Adamowski, Jaroslaw (14 February 2017). "Czech, Swiss militaries could lease Airbus A400M from Germany". Defense News. Warsaw, Poland.

- "Germany to form A400M Multinational Air Transport Unit with Hungary". Janes.com. 18 September 2020. Retrieved 11 January 2021.

- Rahmat, Ridzwan (19 January 2017). "Indonesia approves acquisition of five Airbus A400Ms for USD2 billion". IHS Jane's 360. Singapore.

- "Airbus Signs LOI with Indonesia's Pelita Air Services on A400M Transport Aircraft". Archived from the original on 12 March 2018. Retrieved 12 March 2018.

- "Indonesia trade agency proposes cargo use for A400M". Archived from the original on 12 March 2018. Retrieved 12 March 2018.

- "Indonesia Ministry of Defence orders two Airbus A400Ms | Airbus". www.airbus.com. 17 November 2021. Retrieved 18 November 2021.

- "The Republic of Kazakhstan orders two Airbus A400Ms". Airbus. 1 September 2021.

- "A400M price tag stays at RM600m each." Malay Mail, 13 November 2009. Archived 28 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- "South Africa signs for A400M transports." Flight International, 3 May 2005.

- Roberts, Janice. "Airbus refunds A400M payments to Armscor." Moneyweb, 19 December 2011.

- Grevatt, Jon. "South Korea confirms potential aircraft swap deal with Spain". Jane's. Archived from the original on 24 February 2019. Retrieved 24 February 2019.

- Hoyle, Craig (18 December 2014). "Germany receives first A400M airlifter". FlightGlobal. Retrieved 22 May 2020.

- "Durchbruch im Streit über A400M" (German) Archived 28 October 2010 at the Wayback Machine Sueddeutsche Zeitung. Retrieved: 27 October 2010.

- "Airbus Military's initial A400M is delivered to the French Air Force". airbus.com. 1 August 2013. Retrieved 22 May 2020.

- "Spain receives its first A400M transport". flightglobal.com. 17 November 2016. Archived from the original on 18 November 2016.

- "Evaluación de los Programas Especiales de Armamento (PEAs)" (in Spanish). Archived 24 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine Ministerio de Defensa, Madrid (Grupo Atenea), September 2011.

- "Avión de transporte A400M." Archived 7 May 2018 at the Wayback Machine Ministerio de Defensa. Retrieved: 6 May 2018.

- the Royal Air Force has now received its 21st A400M, Twitter, retrieved 11 October 2022

- "UK's first A400M arrives at Brize Norton home". flightglobal.com. Archived from the original on 2 July 2015. Retrieved 9 May 2015.

- "UK approaches Airbus Military, Thales for A400M training service" Archived 22 May 2014 at the Wayback Machine flightglobal.com, August 2010.

- "UK planning to purchase additional A400M transport aircraft". UK Defence Journal. 6 January 2022. Retrieved 7 January 2022.

- "Airbus Defence and Space delivers A400M to Turkish Air Force". airbus-group.com. Archived from the original on 22 May 2014. Retrieved 22 May 2014.

- "Turkey completes its A400M fleet with 10th delivery!". www.defenceturkey.com. Retrieved 1 June 2021.

- Hoyle, Craig. "Belgium’s first Atlas caps A400M deliveries for year". Flight Global, 22 December 2020.

- "Luxembourg Takes Delivery Of A400M | Aviation Week Network". aviationweek.com.

- "Airbus-Lieferung wird auf 2020 verschoben" (in German). lessentiel.lu. 9 March 2018. Archived from the original on 12 March 2018.

- "Fourth and Final A400M Delivered to Malaysia". Airheads Fly. 9 March 2017. Archived from the original on 10 March 2017.

- Alexander, Harriet (9 May 2015). "Video: Military plane crashes during test flight near Seville". Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 24 June 2018.

- Teresa López Pavón (9 May 2015). "Cuatro muertos tras estrellarse un avión militar A-400M en pruebas junto al aeropuerto de Sevilla". ELMUNDO (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 9 May 2015.

- "Fatal A400M crash linked to data-wipe mistake". BBC News. 10 June 2015. Archived from the original on 10 June 2015. Retrieved 10 June 2015.

- Airbus (15 May 2020). "A400M Specifications". Airbus Defence & Space. Archived from the original on 18 October 2015. Retrieved 13 May 2020.

- "A400M Delivery to the point of need". Airbus. Retrieved 31 May 2020.

- "Das Transportflugzeug Airbus A400M". German Air Force. Retrieved 11 January 2022.

External links

- Official website

- OCCAR A400M page

- Atlas shoulders the load Operation Ruman, the operational debut of the RAF A400M Atlas in a major humanitarian airlift (Royal Aeronautical Society, January 2018)

На других языках

[de] Airbus A400M

Der Airbus A400M Atlas[3] ist ein militärisches Transportflugzeug von Airbus Defence and Space. Der A400M ersetzt bzw. ergänzt in den Luftwaffen von sieben europäischen NATO-Staaten zunehmend den größtenteils veralteten Bestand an taktischen Transportflugzeugen der Typen Transall C-160 und Lockheed C-130 Hercules. Er zeichnet sich gegenüber diesen durch höhere Nutzlast, Transportvolumen, Geschwindigkeit und Reichweite aus und steigert damit die europäischen Fähigkeiten im Bereich des strategischen Lufttransports. Der viermotorige Schulterdecker ist wie seine Vorgänger mit Turboprop-Triebwerken und einer befahrbaren Heckrampe ausgestattet, kann von kurzen, unbefestigten Pisten operieren sowie Fallschirmspringer und Lasten aus der Luft absetzen. Zum Einsatzspektrum zählen auch die Verwendungen als Lazarett- und Tankflugzeug.[4] Die für das Projekt notwendige Neuentwicklung der Triebwerke EPI TP400-D6 übernahm das eigens gegründete Firmenkonsortium Europrop International.- [en] Airbus A400M Atlas

[fr] Airbus A400M Atlas

L'Airbus A400M Atlas[10],[Note 1] est un avion de transport militaire polyvalent conçu par Airbus Military, entré en service en 2013[11]. Au 28 février 2021, il totalise 174 commandes dont 100 livrées[12].[it] Airbus A400M

L'Airbus A400M Atlas è un quadrimotore turboelica da trasporto militare tattico e strategico ad ala alta sviluppato dal consorzio europeo Airbus.[ru] Airbus A400M

Airbus A400M Atlas — четырёхмоторный турбовинтовой военно-транспортный самолёт производства европейского концерна Airbus Military (подразделение Airbus Group). Первый полёт состоялся 11 декабря 2009 года. На вооружение принят в 2010 году[уточнить].Другой контент может иметь иную лицензию. Перед использованием материалов сайта WikiSort.org внимательно изучите правила лицензирования конкретных элементов наполнения сайта.

WikiSort.org - проект по пересортировке и дополнению контента Википедии