avia.wikisort.org - Aeroplane

The Bell Boeing V-22 Osprey is an American multi-mission, tiltrotor military aircraft with both vertical takeoff and landing (VTOL) and short takeoff and landing (STOL) capabilities. It is designed to combine the functionality of a conventional helicopter with the long-range, high-speed cruise performance of a turboprop aircraft.

| V-22 Osprey | |

|---|---|

| |

| An MV-22 used during a MAGTF demonstration during the 2014 Miramar Air Show | |

| Role | V/STOL military transport aircraft |

| National origin | United States |

| Manufacturer | Bell Helicopter Boeing Defense, Space & Security |

| First flight | 19 March 1989 |

| Introduction | 13 June 2007[1] |

| Status | In service |

| Primary users | United States Marine Corps United States Air Force United States Navy Japan Ground Self-Defense Force |

| Produced | 1988–present |

| Number built | 400 as of 2020[2] |

| Developed from | Bell XV-15 |

In 1980, the failure of Operation Eagle Claw (during the Iran hostage crisis) underscored that there were military roles for which neither conventional helicopters nor fixed-wing transport aircraft were well-suited. The United States Department of Defense (DoD) initiated a program to develop an innovative transport aircraft with long-range, high-speed, and vertical-takeoff capabilities, and the Joint-service Vertical take-off/landing Experimental (JVX) program officially commenced in 1981. A partnership between Bell Helicopter and Boeing Helicopters was awarded a development contract in 1983 for the V-22 tiltrotor aircraft. The Bell Boeing team jointly produces the aircraft.[3] The V-22 first flew in 1989 and began flight testing and design alterations; the complexity and difficulties of being the first tiltrotor for military service led to many years of development.

The United States Marine Corps (USMC) began crew training for the MV-22B Osprey in 2000 and fielded it in 2007; it supplemented and then replaced their Boeing Vertol CH-46 Sea Knights. The U.S. Air Force (USAF) fielded its version of the tiltrotor, the CV-22B, in 2009. Since entering service with the Marine Corps and Air Force, the Osprey has been deployed in transportation and medevac operations over Iraq, Afghanistan, Libya, and Kuwait. The U.S. Navy planned to use the CMV-22B for carrier onboard delivery duties beginning in 2021.[needs update]

Development

Origins

The failure of Operation Eagle Claw, the Iran hostage rescue mission, in 1980 demonstrated to the United States military a need[4][5] for "a new type of aircraft, that could not only take off and land vertically but also could carry combat troops, and do so at speed."[6] The U.S. Department of Defense began the JVX aircraft program in 1981, under U.S. Army leadership.[7]

The defining mission of the USMC has been to perform an amphibious landing; the service quickly became interested in the JVX program. Recognizing that a concentrated force was vulnerable to a single nuclear weapon, airborne solutions with good speed and range allowed for rapid dispersal,[8] and their CH-46 Sea Knights were wearing out.[9] Without replacement, the USMC and the Army merging was a lingering threat,[10][11] akin to President Truman's proposal following World War II.[12] The Office of the Secretary of Defense and Navy administration opposed the tiltrotor project, but congressional pressure proved persuasive.[13]

The Navy and USMC were given the lead in 1983.[7][14][15] The JVX combined requirements from the USMC, USAF, Army and Navy.[16][17] A request for proposals was issued in December 1982 for preliminary design work. Interest was expressed by Aérospatiale, Bell Helicopter, Boeing Vertol, Grumman, Lockheed, and Westland. Contractors were encouraged to form teams. Bell partnered with Boeing Vertol to submit a proposal for an enlarged version of the Bell XV-15 prototype on 17 February 1983. Being the only proposal received, a preliminary design contract was awarded on 26 April 1983.[18][19]

The JVX aircraft was designated V-22 Osprey on 15 January 1985; by that March, the first six prototypes were being produced, and Boeing Vertol was expanded to handle the workload.[20][21] Work was split evenly between Bell and Boeing. Bell Helicopter manufactures and integrates the wing, nacelles, rotors, drive system, tail surfaces, and aft ramp, as well as integrates the Rolls-Royce engines and performs final assembly. Boeing Helicopters manufactures and integrates the fuselage, cockpit, avionics, and flight controls.[3][22] The USMC variant received the MV-22 designation, and the USAF variant received CV-22; this was reversed from normal procedure to prevent USMC Ospreys from having a conflicting CV designation with aircraft carriers.[23] Full-scale development began in 1986.[24] On 3 May 1986, Bell Boeing was awarded a US$1.714 billion contract for the V-22 by the U.S. Navy. At this point, all four U.S. military services had acquisition plans for the V-22.[25]

The first V-22 was publicly rolled out in May 1988.[26][27] That year, the U.S. Army left the program, citing a need to focus its budget on more immediate aviation programs.[7] In 1989, the V-22 survived two separate Senate votes that could have resulted in cancellation.[28][29] Despite the Senate's decision, the Department of Defense instructed the Navy not to spend more money on the V-22.[30] As development cost projections greatly increased in 1988, Defense Secretary Dick Cheney tried to defund it from 1989 to 1992, but was overruled by Congress,[14][31] which provided unrequested program funding.[32] Multiple studies of alternatives found the V-22 provided more capability and effectiveness with similar operating costs.[33] The Clinton Administration was supportive of the V-22, helping it attain funding.[14]

Flight testing and design changes

The first of six prototypes first flew on 19 March 1989 in the helicopter mode[34] and on 14 September 1989 in fixed-wing mode.[35] The third and fourth prototypes successfully completed the first sea trials on USS Wasp in December 1990.[36] The fourth and fifth prototypes crashed in 1991–92.[37] From October 1992 to April 1993, the V-22 was redesigned to reduce empty weight, simplify manufacture, and reduce build costs; it was designated V-22B.[38] Flights resumed in June 1993 after safety changes were made to the prototypes.[39] Bell Boeing received a contract for the engineering manufacturing development (EMD) phase in June 1994.[38] The prototypes were also modified to resemble the V-22B standard. At this stage, testing focused on flight envelope expansion, measuring flight loads, and supporting the EMD redesign. Flight testing with the early V-22s continued into 1997.[40]

Flight testing of four full-scale development V-22s began at the Naval Air Warfare Test Center, Naval Air Station Patuxent River, Maryland. The first EMD flight took place on 5 February 1997. Testing soon fell behind schedule.[41] The first of four low rate initial production aircraft, ordered on 28 April 1997, was delivered on 27 May 1999. The second sea trials were completed onboard USS Saipan in January 1999.[24] During external load testing in April 1999, a V-22 transported the lightweight M777 howitzer.[42][43]

In 2000, there were two fatal crashes, killing a total of 23 marines, and the V-22 was again grounded while the crashes' causes were investigated and various parts were redesigned.[31] In June 2005, the V-22 completed its final operational evaluation, including long-range deployments, high altitude, desert and shipboard operations; problems previously identified had reportedly been resolved.

U.S. Naval Air Systems Command (NAVAIR) worked on software upgrades to increase the maximum speed from 250 knots (460 km/h; 290 mph) to 270 knots (500 km/h; 310 mph), increase helicopter mode altitude limit from 10,000 feet (3,000 m) to 12,000 feet (3,700 m) or 14,000 feet (4,300 m), and increase lift performance.[45] By 2012, changes had been made to the hardware, software, and procedures in response to hydraulic fires in the nacelles, vortex ring state control issues, and opposed landings;[46][47] reliability has improved accordingly.[48]

An MV-22 landed and refueled onboard Nimitz in an evaluation in October 2012.[49] In 2013, cargo handling trials occurred on Harry S. Truman.[50] In October 2015, NAVAIR tested rolling landings and takeoffs on a carrier, preparing for carrier onboard delivery.[51]

Controversy

Development was protracted and controversial, partly because of large cost increases,[52] some of which were caused by a requirement to fold wings and rotors to fit aboard ships.[53] The development budget was first set at US$2.5 billion in 1986, increasing to a projected US$30 billion in 1988.[31] By 2008, US$27 billion had been spent and another US$27.2 billion was required for planned production numbers.[24] Between 2008 and 2011, the V-22's estimated lifetime cost grew by 61%, mostly for maintenance and support.[54]

Its [The V-22's] production costs are considerably greater than for helicopters with equivalent capability – specifically, about twice as great as for the CH-53E, which has a greater payload and an ability to carry heavy equipment the V-22 cannot ... an Osprey unit would cost around $60 million to produce, and $35 million for the helicopter equivalent.[55]

— Michael E. O'Hanlon, 2002

In 2001, Lieutenant Colonel Odin Lieberman, commander of the V-22 squadron at Marine Corps Air Station New River, was relieved of duty after allegations that he instructed his unit to falsify maintenance records to make it appear more reliable.[24][56] Three officers were implicated for their roles in the falsification scandal.[52]

In October 2007, a Time magazine article condemned the V-22 as unsafe, overpriced, and inadequate;[57] the USMC responded that the article's data was partly obsolete, inaccurate, and held high expectations for any new field of aircraft.[58] In 2011, the controversial defense industry supported Lexington Institute[59][60][61] reported that the average mishap rate per flight hour over the past 10 years was the lowest of any USMC rotorcraft, approximately half of the average fleet accident rate.[62] In 2011, Wired magazine reported that the safety record had excluded ground incidents;[63] the USMC responded that MV-22 reporting used the same standards as other Navy aircraft.[64]

By 2012, the USMC reported fleetwide readiness rate had risen to 68%;[65] however, the DOD's Inspector General later found 167 of 200 reports had "improperly recorded" information.[66] Captain Richard Ulsh blamed errors on incompetence, saying that they were "not malicious" or deliberate.[67] The required mission capable rate was 82%, but the average was 53% from June 2007 to May 2010.[68] In 2010, Naval Air Systems Command aimed for an 85% reliability rate by 2018.[69] From 2009 to 2014, readiness rates rose 25% to the "high 80s", while cost per flight hour had dropped 20% to $9,520 through a rigorous maintenance improvement program that focused on diagnosing problems before failures occur.[70] As of 2015[update], although the V-22 requires more maintenance and has lower availability (62%) than traditional helicopters, it also has a lower mishap rate. The average cost per flight hour is US$9,156,[71] whereas the Sikorsky CH-53E Super Stallion cost about $20,000 per flight hour in 2007.[72] V-22 ownership cost was $83,000 per hour in 2013.[73]

While technically capable of autorotation if both engines fail in helicopter mode, a safe landing is difficult.[74] In 2005, a director of the Pentagon's testing office stated that in a loss of power while hovering below 1,600 feet (490 m), emergency landings "are not likely to be survivable." V-22 pilot Captain Justin "Moon" McKinney stated that: "We can turn it into a plane and glide it down, just like a C-130."[57] A complete loss of power requires both engines to fail, as one engine can power both proprotors via interconnected drive shafts.[75] Though vortex ring state (VRS) contributed to a deadly V-22 accident, flight testing found it to be less susceptible to VRS than conventional helicopters.[4] A GAO report stated that the V-22 is "less forgiving than conventional helicopters" during VRS.[76] Several test flights to explore VRS characteristics were canceled.[77] The USMC trains pilots in the recognition of and recovery from VRS, and has instituted operational envelope limits and instrumentation to help avoid VRS conditions.[31][78]

Production

On 28 September 2005, the Pentagon formally approved full-rate production,[79] increasing from 11 V-22s per year to between 24 and 48 per year by 2012. Of the 458 total planned, 360 are for the USMC, 50 for the USAF, and 48 for the Navy at an average cost of $110 million per aircraft, including development costs.[24] The V-22 had an incremental flyaway cost of $67 million per aircraft in 2008,[80] The Navy had hoped to shave about $10 million off that cost via a five-year production contract in 2013.[81] Each CV-22 cost $73 million in the FY 2014 budget.[82]

On 15 April 2010, the Naval Air Systems Command awarded Bell Boeing a $42.1 million contract to design an integrated processor in response to avionics obsolescence and add new network capabilities.[83] By 2014, Raytheon began providing an avionics upgrade that includes situational awareness and blue force tracking.[84] In 2009, a contract for Block C upgrades was awarded to Bell Boeing.[85] In February 2012, the USMC received the first V-22C, featuring a new radar, additional mission management and electronic warfare equipment.[86] In 2015, options for upgrading all aircraft to the V-22C standard were examined.[87]

On 12 June 2013, the U.S. DoD awarded a $4.9 billion contract for 99 V-22s in production Lots 17 and 18, including 92 MV-22s for the USMC, for completion in September 2019.[88] A provision gives NAVAIR the option to order 23 more Ospreys.[89] As of June 2013, the combined value of all contracts placed totaled $6.5 billion.[90] In 2013, Bell laid off production staff following the US's order being cut to about half of the planned number.[91][92] Production rate went from 40 in 2012 to 22 planned for 2015.[93] Manufacturing robots have replaced older automated machines for increased accuracy and efficiency; large parts are held in place by suction cups and measured electronically.[94][95]

In March 2014, Air Force Special Operations Command issued a Combat Mission Need Statement for armor to protect V-22 passengers. NAVAIR worked with a Florida-based composite armor company and the Army Aviation Development Directorate to develop and deliver the advanced ballistic stopping system (ABSS) by October 2014. Costing $270,000, the ABSS consists of 66 plates fitting along interior bulkheads and deck, adding 800 lb (360 kg) to the aircraft's weight, affecting payload and range. The ABSS can be installed or removed when needed in hours and partially assembled in pieces for partial protection of specific areas. As of May 2015, 16 kits had been delivered to the USAF.[96][97]

In 2015, Bell Boeing set up the V-22 Readiness Operations Center at Ridley Park, Pennsylvania, to gather information from each aircraft to improve fleet performance in a similar manner as the F-35's Autonomic Logistics Information System.[98]

Design

Overview

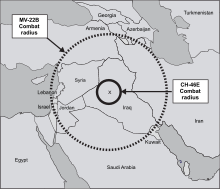

The Osprey is the world's first production tiltrotor aircraft,[99] with one three-bladed proprotor, turboprop engine, and transmission nacelle mounted on each wingtip.[100] It is classified as a powered lift aircraft by the Federal Aviation Administration.[101] For takeoff and landing, it typically operates as a helicopter with the nacelles vertical and rotors horizontal. Once airborne, the nacelles rotate forward 90° in as little as 12 seconds for horizontal flight, converting the V-22 to a more fuel-efficient, higher speed turboprop aircraft.[102] STOL rolling-takeoff and landing capability is achieved by having the nacelles tilted forward up to 45°.[103][104] Other orientations are possible.[105] Pilots describe the V-22 in airplane mode as comparable to the C-130 in feel and speed.[106] It has a ferry range of over 2,100 nmi. Its operational range is 1,100 nmi.[107]

Composite materials make up 43% of the airframe, and the proprotor blades also use composites.[103] For storage, the V-22's rotors fold in 90 seconds and its wing rotates to align, front-to-back, with the fuselage.[108] Because of the requirement for folding rotors, their 38-foot (11.6 m) diameter is 5 feet (1.5 m) less than optimal for vertical takeoff, resulting in high disk loading.[105] Most missions use fixed wing flight 75% or more of the time, reducing wear and tear and operational costs. This fixed wing flight is higher than typical helicopter missions allowing longer range line-of-sight communications for improved command and control.[24]

Exhaust heat from the V-22's engines can potentially damage ships' flight decks and coatings. NAVAIR devised a temporary fix of portable heat shields placed under the engines and determined that a long-term solution would require redesigning decks with heat resistant coating, passive thermal barriers, and ship structure changes. Similar changes are required for F-35B operations.[109] In 2009, DARPA requested solutions for installing robust flight deck cooling.[110] A heat-resistant anti-skid metal spray named Thermion has been tested on USS Wasp.[111]

Propulsion

The V-22's two Rolls-Royce AE 1107C engines are connected by drive shafts to a common central gearbox so that one engine can power both proprotors if an engine failure occurs.[75] Either engine can power both proprotors through the wing driveshaft.[74] However, the V-22 is generally not capable of hovering on one engine.[112] If a proprotor gearbox fails, that proprotor cannot be feathered, and both engines must be stopped before an emergency landing. The autorotation characteristics are poor because of the rotors' low inertia.[74]

In September 2013, Rolls-Royce announced that it had increased the AE-1107C engine's power by 17% via the adoption of a new Block 3 turbine, increased fuel valve flow capacity, and software updates; it should also improve reliability in high-altitude, high-heat conditions and boost maximum payload limitations from 6,000 to 8,000 shp (4,500 to 6,000 kW). A Block 4 upgrade is reportedly being examined, which may increase power by up to 26%, producing close to 10,000 shp (7,500 kW), and improve fuel consumption.[113]

In August 2014, the U.S. military issued a request for information for a potential drop-in replacement for the AE-1107C engines. Submissions must have a power rating of no less than 6,100 shp (4,500 kW) at 15,000 rpm, operate at up to 25,000 ft (7,600 m) at up to 130 degrees Fahrenheit (54 degrees Celsius), and fit into the existing wing nacelles with minimal structural or external modifications.[114] In September 2014, the U.S. Navy, who already purchase engines separately to airframes, was reportedly considering an alternative engine supplier to reduce costs.[115] The General Electric GE38 is one option, giving commonality with the Sikorsky CH-53K King Stallion.[116]

The V-22 has a maximum rotor downwash speed of over 80 knots (92 mph; 150 km/h), more than the 64-knot (74 mph; 119 km/h) lower limit of a hurricane.[117][118] The rotorwash usually prevents the starboard door's usage in hover; the rear ramp is used for rappelling and hoisting instead.[74][119] The V-22 loses 10% of its vertical lift over a tiltwing design when operating in helicopter mode because of the wings' airflow resistance, while the tiltrotor design has better short takeoff and landing performance.[120] V-22s must keep at least 25 ft (7.6 m) of vertical separation between each other to avoid each other's rotor wake, which causes turbulence and potentially control loss.[97]

Avionics

The V-22 is equipped with a glass cockpit, which incorporates four multi-function displays (MFDs, compatible with night-vision goggles)[74] and one shared central display unit, to display various images including: digimaps, imagery from the Turreted forward-looking infrared system[121] primary flight instruments, navigation (TACAN, VOR, ILS, GPS, INS), and system status. The flight director panel of the cockpit management system allows for fully coupled (autopilot) functions that take the aircraft from forward flight into a 50 ft (15 m) hover with no pilot interaction other than programming the system.[122] The fuselage is not pressurized, and personnel must wear on-board oxygen masks above 10,000 feet.[74]

The V-22 has triple-redundant fly-by-wire flight control systems; these have computerized damage control to automatically isolate damaged areas.[123][124] With the nacelles pointing straight up in conversion mode at 90° the flight computers command it to fly like a helicopter, cyclic forces being applied to a conventional swashplate at the rotor hub. With the nacelles in airplane mode (0°) the flaperons, rudder, and elevator fly similar to an airplane. This is a gradual transition, occurring over the nacelles' rotation range; the lower the nacelles, the greater effect of the airplane-mode control surfaces.[125] The nacelles can rotate past vertical to 97.5° for rearward flight.[126][127] The V-22 can use the "80 Jump" orientation with the nacelles at 80° for takeoff to quickly achieve high altitude and speed.[105] The controls automate to the extent that it can hover in low wind without hands on the controls.[105][74]

New USMC V-22 pilots learn to fly helicopter and multiengine fixed-wing aircraft before the tiltrotor.[128] Some V-22 pilots believe that former fixed-wing pilots may be preferable over helicopter users, as they are not trained to constantly adjust the controls in hover. Others say that experience with helicopters' hovering and precision is most important.[105][74] As of April 2021[update] the US military does not track whether fixed-wing or helicopter pilots transition more easily to the V-22, according to USMC Colonel Matthew Kelly, V-22 project manager. He said that fixed-wing pilots are more experienced at instrument flying, while helicopter pilots are more experienced at scanning outside when the aircraft is moving slowly.[106]

Armament

The V-22 can be armed with one 7.62×51mm NATO (.308 in caliber) M240 machine gun or .50 in caliber (12.7 mm) M2 machine gun on the rear loading ramp. A 12.7 mm (.50 in) GAU-19 three-barrel Gatling gun mounted below the nose was studied.[129] BAE Systems developed a belly-mounted, remotely operated gun turret system,[130] the Interim Defense Weapon System (IDWS);[131] it is remotely operated by a gunner, targets are acquired via a separate pod using color television and forward looking infrared imagery.[132] The IDWS was installed on half of the V-22s deployed to Afghanistan in 2009;[131] it found limited use because of its 800 lb (360 kg) weight and restrictive rules of engagement.[133]

There were 32 IDWSs available to the USMC in June 2012; V-22s often flew without it as the added weight reduced cargo capacity. The V-22's speed allows it to outrun conventional support helicopters, thus a self-defense capability was required on long-range independent operations. The infrared gun camera proved useful for reconnaissance and surveillance. Other weapons were studied to provide all-quadrant fire, including nose guns, door guns, and non-lethal countermeasures to work with the current ramp-mounted machine gun and the IDWS.[134]

In 2014, the USMC studied new weapons with "all-axis, stand-off, and precision capabilities", akin to the AGM-114 Hellfire, AGM-176 Griffin, Joint Air-to-Ground Missile, and GBU-53/B SDB II.[135] In November 2014, Bell Boeing conducted self-funded weapons tests, equipping a V-22 with a pylon on the front fuselage and replacing the AN/AAQ-27A EO camera with an L-3 Wescam MX-15 sensor/laser designator. 26 unguided Hydra 70 rockets, two guided APKWS rockets, and two Griffin B missiles were fired over five flights. The USMC and USAF sought a traversable nose-mounted weapon connected to a helmet-mounted sight; recoil complicated integrating a forward-facing gun.[136] A pylon could carry 300 lb (140 kg) of munitions.[137] However, by 2019, the USMC opted for IDWS upgrades over adopting new weapons.[138]

Refueling capability

Boeing is developing a roll-on/roll-off aerial refueling kit, which would give the V-22 the ability to refuel other aircraft. Having an aerial refueling capability that can be based on Wasp-class amphibious assault ships would increase the F-35B's strike power, removing reliance on refueling assets solely based on large Nimitz-class aircraft carriers or land bases. The roll-on/roll-off kit can also be applicable to intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (ISR) functions.[139] Boeing funded a non-functional demonstration on a VMX-22 aircraft; a prototype kit was successfully tested with an F/A-18 on 5 September 2013.[140]

The high-speed version of the hose/drogue refueling system can be deployed at 185 knots (213 mph; 343 km/h) and function at up to 250 knots (290 mph; 460 km/h). A mix of tanks and a roll-on/roll-off bladder house up to 12,000 lb (5,400 kg) of fuel. The ramp must open to extend the hose, then raised once extended. It can refuel rotorcraft, needing a separate drogue used specifically by helicopters and a converted nacelle.[141] Many USMC ground vehicles can run on aviation fuel, a refueling V-22 could service these. In late 2014, it was stated that V-22 tankers could be in use by 2017,[142] but contract delays pushed IOC to late 2019.[143] As part of a 26 May 2016 contract award to Boeing,[144] Cobham was contracted to adapt their FR-300 hose drum unit as used by the KC-130 in October 2016.[145] While the Navy has not declared its interest in the capability, it could be leveraged later on.[146]

Operational history

In October 2019, the fleet of 375 V-22s operated by the U.S. Armed Forces surpassed the 500,000 flight hour mark.[147]

U.S. Marine Corps

Since March 2000, VMMT-204 has conducted training for the type. In December 2005, Lieutenant General James Amos, commander of II Marine Expeditionary Force, accepted delivery of the first batch of MV-22s. The unit reactivated in March 2006 as the first MV-22 squadron, redesignated as VMM-263. In 2007, HMM-266 became Marine Medium Tiltrotor Squadron 266 (VMM-266)[148] and reached initial operational capability.[1] It started replacing the CH-46 Sea Knight in 2007; the CH-46 was retired in October 2014.[149][150] On 13 April 2007, the USMC announced the first V-22 combat deployment at Al Asad Airbase, Iraq.[151][152]

V-22s in Iraq's Anbar province were used for transport and scout missions. General David Petraeus, the top U.S. military commander in Iraq, used one to visit troops on Christmas Day 2007;[153] as did Barack Obama during his 2008 presidential campaign tour in Iraq.[154] USMC Col. Kelly recalled how visitors were reluctant to fly on the unfamiliar aircraft, but after seeing its speed and ability to fly above ground fire, "All of a sudden, the entire flight schedule was booked. No senior officer wanted to go anywhere unless they could fly on the V-22".[106] Obtaining spares proved problematic.[155] By July 2008, the V-22 had flown 3,000 sorties totaling 5,200 hours in Iraq.[156] General George J. Trautman III praised its greater speed and range over legacy helicopters, saying "it turned his battle space from the size of Texas into the size of Rhode Island."[157] Despite attacks by man-portable air-defense systems and small arms, none were lost to enemy fire by late 2009.[158]

A Government Accountability Office study stated that by January 2009, the 12 MV-22s in Iraq had completed all assigned missions; mission capable rates averaged 57% to 68%, and an overall full mission capable rate of 6%. It also noted weaknesses in situational awareness, maintenance, shipboard operations and transport capability.[159][160] The report concluded: "deployments confirmed that the V-22's enhanced speed and range enable personnel and internal cargo to be transported faster and farther than is possible with the legacy helicopters".[159]

MV-22s deployed to Afghanistan in November 2009 with VMM-261;[161][162] it saw its first offensive combat mission, Operation Cobra's Anger, on 4 December 2009. V-22s assisted in inserting 1,000 USMC and 150 Afghan troops into the Now Zad Valley of Helmand Province in southern Afghanistan to disrupt Taliban operations.[131] General James Amos stated that Afghanistan's MV-22s had surpassed 100,000 flight hours, calling it "the safest airplane, or close to the safest airplane" in the USMC inventory.[163] The V-22's Afghan deployment was set to end in late 2013 with the drawdown of combat operations; however, VMM-261 was directed to extend operations for casualty evacuation, being quicker than helicopters enabled more casualties to reach a hospital within the 'golden hour'; they were fitted with medical equipment such as heart monitors and triage supplies.[164]

In January 2010, the MV-22 was sent to Haiti as part of Operation Unified Response relief efforts after an earthquake, the type's first humanitarian mission.[165] In March 2011, two MV-22s from Kearsarge helped rescue a downed USAF F-15E crew member during Operation Odyssey Dawn.[166][167] On 2 May 2011, following Operation Neptune's Spear, the body of Osama bin Laden, founder of the al-Qaeda terrorist group, was flown by a MV-22 to the aircraft carrier Carl Vinson in the Arabian Sea, prior to his burial at sea.[168]

In 2013, several MV-22s received communications and seating modifications to support the Marine One presidential transport squadron because of the urgent need for CH-53Es in Afghanistan.[169][170] In May 2010, Boeing announced plans to submit the V-22 for the VXX presidential transport replacement.[171]

From 2 to 5 August 2013, two MV-22s completed the longest distance Osprey tanking mission to date. Flying from Marine Corps Air Station Futenma in Okinawa alongside two KC-130J tankers, they flew to Clark Air Base in the Philippines on 2 August; then to Darwin, Australia, on 3 August; to Townsville, Australia, on 4 August; and finally rendezvoused with Bonhomme Richard on 5 August.[172]

In 2013, the USMC formed an intercontinental response force, the Special Purpose Marine Air-Ground Task Force – Crisis Response – Africa,[173] using V-22s outfitted with specialized communications gear.[174] In 2013, following Typhoon Haiyan, 12 MV-22s of the 3rd Marine Expeditionary Brigade were deployed to the Philippines for disaster relief operations;[175] its abilities were described as "uniquely relevant", flying faster and with greater payloads while moving supplies throughout the island archipelago.[176]

U.S. Air Force

The USAF's first operational CV-22 was delivered to the 58th Special Operations Wing (58th SOW) at Kirtland Air Force Base, New Mexico, in March 2006. Early aircraft were delivered to the 58th SOW and used for training personnel for special operations use.[177] On 16 November 2006, the USAF officially accepted the CV-22 in a ceremony conducted at Hurlburt Field, Florida.[178] The USAF's first operational deployment sent four CV-22s to Mali in November 2008 in support of Exercise Flintlock. The CV-22s flew nonstop from Hurlburt Field, Florida, with in-flight refueling.[4] AFSOC declared that the 8th Special Operations Squadron reached Initial Operational Capability in March 2009, with six CV-22s in service.[179]

In December 2013, three CV-22s came under small arms fire while trying to evacuate American civilians in Bor, South Sudan, during the 2013 South Sudanese political crisis; the aircraft flew 500 mi (800 km) to Entebbe, Uganda, after the mission was aborted. South Sudanese officials stated that the attackers were rebels.[180][181] The CV-22s had flown to Bor over three countries across 790 nmi (910 mi; 1,460 km). The formation was hit 119 times, wounding four crew and causing flight control failures and hydraulic and fuel leaks on all three aircraft. Fuel leaks resulted in multiple air-to-air refuelings en route.[182] After the incident, AFSOC developed optional armor floor panels.[96]

The USAF found that "CV-22 wake modeling is inadequate for a trailing aircraft to make accurate estimations of safe separation from the preceding aircraft."[183] In 2015, the USAF sought to configure the CV-22 to perform combat search and rescue in addition to its long-range special operations transport mission. It would complement the HH-60G Pave Hawk and planned HH-60W rescue helicopters, being employed in scenarios where high speed is better suited to search and rescue than more nimble but slower helicopters.[184]

U.S. Navy

The V-22 program originally included Navy 48 HV-22s, but none were ordered.[24] In 2009, it was proposed that it replace the C-2 Greyhound for carrier onboard delivery (COD) duties. One advantage of the V-22 is the ability to deliver supplies and people between non-carrier ships beyond helicopter range.[185][186] Proponents said that it is capable of similar speed, payload capacity, and lift performance to the C-2, and can carry greater payloads over short ranges, up to 20,000 lb, including suspended external loads. The C-2 can only deliver cargo to carriers, requiring further distribution to smaller vessels via helicopters, while the V-22 is certified for operating upon amphibious ships, aircraft carriers, and logistics ships. It could also take some helicopter roles by fitting a 600 lb hoist to the ramp and a cabin configuration for 12 non-ambulatory patients and 5 seats for medical attendants.[187] Bell and P&W designed a frame for the V-22 to transport the Pratt & Whitney F135 engine of the Lockheed Martin F-35.[188]

On 5 January 2015, the Navy and USMC signed a memorandum of understanding to buy the V-22 for the COD mission.[189] Initially designated HV-22, four aircraft were bought each year from 2018 to 2020.[190] It incorporates an extended-range fuel system for an 1,150 nmi (1,320 mi; 2,130 km) unrefueled range, a high-frequency radio for over-the-horizon communications, and a public address system to communicate with passengers;[191][192] the range increase comes from extra fuel bladders[193] through larger external sponsons, the only external difference from other variants. Its primary mission is long-range logistics; other conceivable missions include personnel recovery and special warfare.[194] In February 2016, the Navy officially designated it as the CMV-22B. The Navy's Program of Record originally called for 48 aircraft, it later determined that only 44 were required. Production began in FY 2018, and deliveries start in 2020.[196][197]

The Navy ordered the first 39 CMV-22Bs in June 2018; initial operating capability is anticipated to be achieved in 2021, with fielding to the fleet by the mid-2020s.[198] The first CMV-22B made its initial flight in December 2019.[199] The first deployment began in summer 2021 aboard the USS Carl Vinson.[200]

Japan Self-Defense Forces

In 2012, former Defense Minister Satoshi Morimoto ordered an investigation of the costs of V-22 operations. The V-22's capabilities exceeded current Japan Self-Defense Forces helicopters in terms of range, speed and payload. The ministry anticipated deployments to the Nansei Islands and the Senkaku Islands, as well as in multinational cooperation with the U.S.[201] In November 2014, the Japanese Ministry of Defense decided to procure 17 V-22s.[202] The first V-22 for Japan undertook its first flight in August 2017[203] and the aircraft began delivery to the Japanese military in 2020.[204]

In September 2018, the Japanese Ministry of Defense decided to delay the deployment of the first five MV-22Bs it had received amid opposition and ongoing negotiations in the Saga Prefecture, where the aircraft are to be based.[205] On 8 May 2020, the first two of the five aircraft were delivered to the JGSDF at Kisarazu Air Field after failing to reach an agreement with Saga prefecture residents.[206] It is planned to eventually station some V-22s on board the Izumo-class helicopter destroyers.

Potential operators

India

In 2015, the Indian Aviation Research Centre showed interest in acquiring four V-22s for personnel evacuation in hostile conditions, logistic supplies, and deployment of the Special Frontier Force in border areas. US V-22s performed relief operations after the April 2015 Nepal earthquake.[207] The Indian Navy also studied the V-22 rather than the E-2D for airborne early warning and control to replace the short-range Kamov Ka-31.[208] India is interested in purchasing six attack version V-22s for rapid troop insertion in border areas.[209][210]

Indonesia

On 6 July 2020, the U.S. State Department announced that they had approved a possible Foreign Military Sale to Indonesia of eight Block C MV-22s and related equipment for an estimated cost of $2 billion. The U.S. Defense Security Cooperation Agency notified Congress of this possible sale.[211]

Israel

On 22 April 2013, an agreement was signed to sell six V-22 to the Israeli Air Force.[212] By the end of 2016, Israel had not ordered the V-22 and was instead interested in buying the C-47 Chinook helicopter or the CH-53K helicopter.[213] As of 2017, Israel had frozen its evaluation of the V-22, "with a senior defence source indicating that the tiltrotor is unable to perform some missions currently conducted using its Sikorsky CH-53 transport helicopters."[214]

Variants

- V-22A

- Pre-production full-scale development aircraft used for flight testing. These are unofficially considered A-variants after the 1993 redesign.[215]

- CV-22B

- U.S. Air Force variant for the U.S. Special Operations Command. It conducts long-range special operations missions and is equipped with extra wing fuel tanks, an AN/APQ-186 terrain-following radar, and other equipment such as the AN/ALQ-211,[216][217] and AN/AAQ-24 Nemesis Directional Infrared Counter Measures.[218] The fuel capacity is increased by 588 gallons (2,230 L) with two inboard wing tanks; three auxiliary tanks (200 or 430 gal) can also be added in the cabin.[219] The CV-22 replaced the MH-53 Pave Low.[24]

- MV-22B

- U.S. Marine Corps variant. The Marine Corps is the lead service in the V-22's development. The Marine Corps variant is an assault transport for troops, equipment and supplies, capable of operating from ships or expeditionary airfields ashore. It replaced the Marine Corps' CH-46E and CH-53D fleets.[220][221]

- CMV-22B

- U.S. Navy variant for the carrier onboard delivery role. Similar to the MV-22B but includes an extended-range fuel system, a high-frequency radio, and a public address system.

- EV-22

- Proposed airborne early warning and control variant. The Royal Navy studied this variant as a replacement for its current fleet of carrier-based Sea King ASaC.7 helicopters.[222]

- HV-22

- The U.S. Navy considered an HV-22 to provide combat search and rescue, delivery and retrieval of special warfare teams along with fleet logistic support transport. It chose the MH-60S for this role in 2001.[223][224]

- SV-22

- Proposed anti-submarine warfare variant. The U.S. Navy studied the SV-22 in the 1980s to replace S-3 and SH-2 aircraft.[225]

Operators

Japan

Japan

United States

United States

- United States Air Force[227]

- United States Marine Corps[227]

- United States Navy – 44 CVM-22Bs on order, with deliveries to start in 2020.[196][197]

Accidents

The V-22 Osprey has had 13 hull-loss accidents with a total of 51 fatalities. During testing from 1991 to 2000, there were four crashes resulting in 30 fatalities.[31] Since becoming operational in 2007, the V-22 has had eight crashes resulting in 16 fatalities and several minor incidents.[252][253] The aircraft's accident history has generated some controversy over its perceived safety issues.[254]

Aircraft on display

- 163911 – V-22A on display at the Aviation Memorial at Marine Corps Air Station New River in Jacksonville, North Carolina.[255][256]

- 163913 – V-22A on display at the American Helicopter Museum & Education Center in West Chester, Pennsylvania.[257][258]

- 99-0021 (formerly 164939) – CV-22B on display at the National Museum of the United States Air Force at Wright-Patterson AFB in Dayton, Ohio.[259]

- 164940 – MV-22B on display at the Patuxent River Naval Air Museum in Lexington Park, Maryland.[260]

Specifications (MV-22B)

Data from Norton,[261] Boeing,[262] Bell Guide,[103] Naval Air Systems Command,[263] and USAF CV-22 fact sheet[216]

General characteristics

- Crew: 3–4 (pilot, copilot and 1 or 2 flight engineers/crew chiefs/loadmasters/gunners)

- Capacity:

- Length: 57 ft 4 in (17.48 m)

- Length folded: 62 ft 7.6 in (19.091 m)

- Wingspan: 45 ft 10 in (13.97 m)

- Width: 84 ft 6.8 in (25.776 m) including rotors

- Width folded: 18 ft 5 in (5.61 m)

- Height: 22 ft 1 in (6.73 m) engine nacelles vertical

- 17 ft 7.8 in (5 m) to top of tailfins

- Height folded: 18 ft 1 in (5.51 m)

- Wing area: 301.4 sq ft (28.00 m2)

- Empty weight: 31,818 lb (14,432 kg)

- Operating weight, empty: 32,623 lb (14,798 kg)

- Gross weight: 39,500 lb (17,917 kg)

- Combat weight: 42,712 lb (19,374 kg)

- Maximum take-off weight VTO: 47,500 lb (21,546 kg)

- Maximum take-off weight STO: 55,000 lb (24,948 kg)

- Maximum take-off weight STO, ferry: 60,500 lb (27,442 kg)

- Fuel capacity:

Ferry maximum 4,451 US gal (3,706 imp gal; 16,850 L) of JP-4 / JP-5 / JP-8 to MIL-T-5624

- 2,436 US gal (2,028 imp gal; 9,220 L) in optional cabin auxiliary tank

- 1,228 US gal (1,023 imp gal; 4,650 L) in three sponson partial self-sealing tanks

- 787 US gal (655 imp gal; 2,980 L) in ten wing self-sealing tanks

- 1.93 US gal (1.61 imp gal; 7.3 L) engine oil

- 25.375 US gal (21.129 imp gal; 96.05 L) transmission oil

- Powerplant: 2 × Rolls-Royce T406-AD-400 turboprop/turboshaft engines, 6,150 hp (4,590 kW) each maximum at 15,000 rpm at sea level, 59 °F (15 °C)

- 5,890 hp (4,392 kW) maximum continuous at 15,000 rpm at sea level, 59 °F (15 °C)

- Main rotor diameter: 2 × 38 ft (12 m)

- Main rotor area: 2,268 sq ft (210.7 m2) 3-bladed

Performance

- Maximum speed: 275 kn (316 mph, 509 km/h) [266]

- 305 kn (565 km/h; 351 mph) at 15,000 ft (4,600 m)[267]

- Stall speed: 110 kn (130 mph, 200 km/h) [74]

- Range: 879 nmi (1,012 mi, 1,628 km)

- Combat range: 390 nmi (450 mi, 720 km)

- Ferry range: 2,230 nmi (2,570 mi, 4,130 km)

- Service ceiling: 25,000 ft (7,600 m)

- g limits:

- g limits, helicopter mode:

- +3 −0.5 at 39,500 lb (17,917 kg)

- +2.77 −0.46 at 42,712 lb (19,374 kg)

- +2.5 −0.42 at 47,500 lb (21,546 kg)

- g limits, airplane mode:

- +4 −1 at 39,500 lb (17,917 kg)

- +3.7 −0.92 at 42,712 lb (19,374 kg)

- +3.3 −0.84 at 47,500 lb (21,546 kg)

- +2.87 −0.72 at 55,000 lb (24,948 kg)

- +2.61 −0.65 at 60,500 lb (27,442 kg)

- Maximum glide ratio: 4.5:1[74]

- Rate of climb: 2,320–4,000 ft/min (11.8–20.3 m/s) [74]

- Wing loading: 20.9 lb/sq ft (102 kg/m2) at 47,500 lb (21,546 kg)

- Power/mass: 0.259 hp/lb (0.426 kW/kg)

Armament

- 1× 7.62 mm (.308 in) M240 machine gun or .50 in (12.7 mm) M2 Browning machine gun on ramp, removable

- 1× 7.62 mm (.308 in) GAU-17 minigun, belly-mounted, retractable, video remote control in the Remote Guardian System [optional][132][268]

Avionics

- AN/ARC-182 VHF/UHF radio

- KY-58 VHF/UHF encryption

- ANDVT HF encryption

- AN/AAR-47 Missile Approach Warning System

- AN/AYK-14 Mission Computers

- APQ-168 Multifunction radar

Notable appearances in media

See also

Related development

- AgustaWestland AW609

- Bell Boeing Quad TiltRotor

- Bell V-280 Valor

- Bell XV-15

Aircraft of comparable role, configuration, and era

- Canadair CL-84

- LTV XC-142

Related lists

- List of military aircraft of the United States

- List of VTOL aircraft

References

- "Osprey Deemed Ready for Deployment". U.S. Marine Corps. 14 June 2007. Archived from the original on 1 December 2016. Retrieved 19 June 2019.

- Brother, Eric. "BBell Boeing delivers 400th V-22 Osprey tiltrotor aircraft". Aerospace Manufacturing and Design, 11 June 2020. Retrieved 22 June 2020.

- "V-22 Osprey Backgrounder". Archived 6 February 2010 at the Wayback Machine Boeing Defense, Space & Security, February 2010.

- Kreisher, Otto. "Finally, the Osprey". Archived 11 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine Air Force Magazine, February 2009.

- Whittle 2010, p. 62.

- Mackenzie, Richard (writer). "Flight of the V-22 Osprey" (Television production). Archived 28 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine Mackenzie Productions for Military Channel, 7 April 2008. Retrieved 29 March 2009.

- Norton 2004, p. 35.

- Whittle 2010, p. 55.

- Whittle 2010, p. 91.

- Whittle 2010, p. 87: "As Kelly saw it, the future of the Marine Corps was riding on it."

- Whittle 2010, p. 155.

- Whittle 2010, pp. 53, 55–56.

- Scroggs, Stephen K. "Army Relations with Congress: Thick Armor, Dull Sword, Slow Horse" p. 232. Greenwood Press, 2000. ISBN 9780313019265.

- Moyers, Al (Director of History and Research). "The Long Road: AFOTEC's Two-Plus Decades of V-22 Involvement". Archived 1 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine Headquarters Air Force Operational Test and Evaluation Center, United States Air Force, 1 August 2007.

- "Chapter 9: Research, Development, and Acquisition". Archived 10 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine Department of the Army Historical Summary: FY 1982. Center of Military History (CMH), United States Army, 1988. ISSN 0092-7880.

- Norton 2004, pp. 22–30.

- "AIAA-83-2726, Bell-Boeing JVX Tilt Rotor Program". Archived 11 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics (AIAA), 16–18 November 1983.

- Norton 2004, pp. 31–33.

- Kishiyama, David. "Hybrid Craft Being Developed for Military and Civilian Use". Archived 7 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine Los Angeles Times, 31 August 1984.

- Adams, Lorraine. "Sales Talk Whirs about Bell Helicopter". Archived 24 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine Dallas Morning News,10 March 1985.

- "Boeing Vertol launches Three-Year, $50 Million Expansion Program". Archived 24 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine The Philadelphia Inquirer, 4 March 1985.

- "Military Aircraft: The Bell-Boeing V-22". Archived 28 March 2010 at the Wayback Machine Bell Helicopter, 2007. Retrieved 30 December 2010.

- Norton 2004, p. 30.

- RL31384, "V-22 Osprey Tilt-Rotor Aircraft: Background and Issues for Congress". Archived 10 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine Congressional Research Service, 22 December 2009.

- Goodrich, Joseph L. "Bell-Boeing team lands contract to develop new tilt-rotor aircraft, 600 jobs expected from $1.714-billion project for Navy". Archived 11 January 2015 at the Wayback Machine Providence Journal, 3 May 1986.

- Belden, Tom. "Vertical-takeoff plane may be the 21st century's intercity bus". Archived 7 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine Toronto Star, 23 May 1988.

- "Tilt-rotor craft flies like copter, plane"[permanent dead link]. Milwaukee Sentinel, 24 May 1988.

- "2 Senators key to fate of Boeing's V-22 Osprey". Archived 24 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine The Philadelphia Inquirer, 6 July 1989.

- Mitchell, Jim. "Gramm defends Osprey's budget cost: Senator makes pitch for V-22 as president stumps for B-2 bomber". Archived 24 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine Dallas Morning News, 22 July 1989.

- "Pentagon halts spending on V-22 Osprey". Archived 7 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine Chicago Tribune, 3 December 1989.

- Berler, Ron. "Saving the Pentagon's Killer Chopper-Plane". Archived 6 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine Wired (CondéNet, Inc), Volume 13, Issue 7, July 2005.

- Norton 2004, p. 49.

- Norton 2004, p. 52.

- "Revolutionary plane passes first test". Toledo Blade, 20 March 1989.

- Mitchell, Jim. "V-22 makes first flight in full airplane mode". Archived 24 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine Dallas Morning News, 15 September 1989.

- Jones, Kathryn. "V-22 tilt-rotor passes tests at sea". Dallas Morning News, 14 December 1990.

- "Navy halts test flights of V-22 as crash investigated". Archived 24 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine Fort Worth Star-Telegram, 13 June 1991.

- Norton 2004, pp. 52–54.

- Norton 2004, p. 55.

- Norton 2004, pp. 55–57.

- Schinasi 2008, p. 23.

- "M777: He Ain't Heavy, He's my Howitzer". Archived 10 September 2012 at the Wayback MachineDefense Industry Daily, 18 July 2012.

- "Lots Riding on V-22 Osprey" Archived 5 January 2012 at the Wayback MachineDefense Industry Daily, 12 March 2007.

- Chavanne, Bettina H. "V-22 To Get Performance Upgrades".[permanent dead link]Aviation Week, 25 June 2009.

- Pappalardo, Joe. "The Osprey's Real Problem Isn't Safety – It's Money". Archived 17 June 2012 at the Wayback MachinePopular Mechanics, 14 June 2012.

- "Software Change Gives V-22 Pilots More Lift Options". Archived 25 September 2011 at the Wayback Machinethebaynet.com. Retrieved 24 April 2012.

- Capaccio, Tony. "V-22 Osprey Aircraft's Reliability Improves in Pentagon Testing". Bloomberg News, 13 January 2012.

- Mass Communication Specialist 3rd Class Renee Candelario, USN (8 October 2012). "MV-22 Osprey Flight Operations Tested Aboard USS Nimitz". NNS121008-13. USS Nimitz Public Affairs. Archived from the original on 24 May 2013.

- Butler, Amy (18 April 2013). "Osprey on the Truman, Fishing for COD". Aviation Week. The McGraw-Hill Companies. Archived from the original on 20 May 2013.

- Tony Osborne (12 November 2015). "V-22 Osprey Testing Could Lead To Higher Takeoff Weights". Aviation Week. Archived from the original on 16 November 2015.

- Bryce, Robert. "Review of political forces that helped shape V-22 program". Archived 27 September 2007 at the Wayback MachineTexas Observer, 17 June 2004.

- Whittle, Richard. "Half-airplane, half-helicopter, totally badass" NY Post, 24 May 2015. Archived on 25 May 2015.

- Capaccio, Tony. "Lifetime cost of V-22s rose 61% in three years". [permanent dead link] Bloomberg News, 29 November 2011.

- O'Hanlon 2002, p. 119.

- Ricks, Thomas E. "Marines Fire Commander Of Ospreys; Alleged Falsification Of Data Investigated". Archived 7 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine The Washington Post, 19 January 2001.

- Thompson, Mark. "V-22 Osprey: A Flying Shame". Archived 11 October 2008 at the Wayback MachineTime, 26 September 2007. Retrieved 8 August 2011.

- Hoellwarth, John. "Leaders, experts slam Time article on Osprey". Archived 10 December 2007 at the Wayback Machine Marine Corps Times (Army Times Publishing Company), 16 October 2007.

- DiMascio, Jen (9 December 2010). "Playing defense – but at a price?". Politico. Archived from the original on 25 May 2015.

- Ackerman, Spencer (12 April 2012). "Defense Industry's Favorite Think Tank Daydreams of Obama Defeat". Wired. Archived from the original on 16 April 2016.

- Silverstein, Ken (1 April 2010). "Mad men – Introducing the defense industry's pay-to-play ad agency". Harper's Magazine.

- "V-22 Is The Safest, Most Survivable Rotorcraft The Marines Have". Archived 3 March 2011 at the Wayback Machine Lexington Institute, February 2011.

- Axe, David. "Marines: Actually, Our Tiltrotor Is 'Effective And Reliable' (Never Mind Those Accidents)". Archived 9 December 2013 at the Wayback MachineWired, 13 October 2011.

- "USMC Statement in Response to Article on the Safety Record of the Marine V-22 Osprey". Archived 16 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine USMC, 13 October 2011.

- "Pentagon watchdog to release classified audit on V-22 Osprey". Marine Corps Times. Archived from the original on 17 August 2013. Retrieved 6 April 2015.

- Capaccio, Tony (25 October 2013). "Pentagon's Inspector General Finds V-22 Readiness Rates Flawed". Bloomberg BusinessWeek. Bloomberg News.

- Lamothe, Dan (2 November 2013). "Are the Marines faking the reliability record of their $79 million superplane?". Foreign Policy. Archived from the original on 3 November 2013.

- Shalal-Esa, Andrea. "U.S. eyes V-22 aircraft sales to Israel, Canada, UAE". Archived 24 September 2015 at the Wayback MachineReuters, 26 February 2012.

- Reed, John. "Boeing to make new multiyear Osprey offer". Navy Times, 5 May 2010.

- Hoffman, Michael. "Osprey Readiness Rates Improved 25% over 5 years Archived 2014-04-13 at the Wayback Machine" DODbuzz, 9 April 2014.

- Whittle, Richard. "Osprey Shows Its Mettle" pp. 23–26. American Helicopter Society / Vertiflite May/June 2015, Vol. 61, No. 3.

- Whittle, Richard. USMC CH-53E Costs Rise With Op Tempo Archived 2 May 2014 at the Wayback MachineRotor & Wing, Aviation Today, January 2007. Quote: For every hour the Corps flies a −53E, it spends 44 maintenance hours fixing it. Every hour a Super Stallion flies it costs about $20,000.

- Magnuson, Stew. "Future of Tilt-Rotor Aircraft Uncertain Despite V-22's Successes" National Defense Industrial Association, July 2015. Archive

- McKinney, Mike. "Flying the V-22" Vertical, 28 March 2012. Archived on 30 April 2014.

- Norton 2004, pp. 98–99.

- Schinasi 2008, p. 16.

- Schinasi 2008, p. 11.

- Gross, Kevin, Lt. Col. U.S. Marine Corps and Tom Macdonald, MV-22 test pilot and Ray Dagenhart, MV-22 lead government engineer. NI_Myth_0904,00.html "Dispelling the Myth of the MV-22". Proceedings: The Naval Institute. September 2004.

- "Osprey OK'd". Archived 6 December 2009 at the Wayback Machine Defense Tech, 28 September 2005.

- "FY 2009 Budget Estimates". p. 133. Archived 3 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine United States Air Force, February 2008.

- Christie, Rebecca (31 May 2007). "DJ US Navy Expects Foreign Interest In V-22 To Ramp Up Next Year". Naval Air Systems Command, United States Navy. Dow Jones Newswires. Archived from the original on 1 December 2016.

- John T. Bennett (14 January 2014). "War Funding Climbs in Omnibus Bill for First Time Since 2010". Defense News. Archived from the original on 1 April 2014.

- Keller, John. "Bell-Boeing to design new integrated avionics processor for V-22 Osprey tiltrotor aircraft". Archived 14 July 2011 at the Wayback MachineMilitaryearospace.com, 18 April 2010.

- "Raytheon wins $250 million contract for V-22 aircraft avionics from US". Archived 23 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine defenseworld.net. Retrieved: 30 December 2010.

- "DOD Contracts". Archived 29 May 2010 at the Wayback Machine United States Department of Defense. 24 November 2009.

- McHale, John. "Block C V-22 Osprey with new radar, cockpit displays, and electronic warfare features delivered to Marines" Archived 22 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Military Embedded Systems, 15 February 2012.

- "LTG Davis Talks To Boeing On Upgrading Half Of Marine V-22 Fleet". Breaking Defense. 13 August 2015. Archived from the original on 23 October 2015. Retrieved 31 October 2015.

- Bell-Boeing award V-22 multi-year contract Archived 6 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine – Flightglobal.com, 12 June 2013

- US military orders additional V-22 Ospreys Archived 1 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine – Shephardmedia.com, 13 June 2013

- Pentagon Signs Multiyear V-22 Deal Archived 3 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine – Aviationweek.com, 13 June 2013

- Berard, Yamil. "Bell to lay off 325 workers as V-22 orders decline". Fort Worth Star-Telegram, 5 May 2014. Retrieved 8 May 2014.

- Berard, Yamil (5 May 2014). "Bell to lay off 325 workers as V-22 orders decline". Fort Worth Star-Telegram. Archived from the original on 2 July 2014.

- Huber, Mark (25 February 2015). "New Programs at Full Speed". Aviation International News. Archived from the original on 2 March 2015.

- Laird, Robbin. "A Hybrid Manufacturer For A Hybrid Airplane" Manufacturing & Technology News, 27 August 2015 Volume 22, No. 10. Archive

- Laird, Robbin. "A Perspective from Visiting the Boeing Plant Near Philadelphia" SLD, 28 May 2015. Archive

- Air Force special ops looks to add armor, firepower to Ospreys[permanent dead link] – Air Force Times, 17 September 2014

- Whittle, Richard. "AFSOC Ospreys Armor Up After Painful Lessons Learned In South Sudan" Breaking Defense, 15 May 2015. Archive

- Batey, Angus (12 July 2016). "ALIS's Children: Networked Prognostics For The V-22". Aviation Week & Space Technology. Penton. Archived from the original on 13 July 2016.

- Mizokami, Kyle (8 February 2019). "The V-22 Osprey: How America's Controversial Tiltrotor Plane Works". Popular Mechanics.

- Croft, John. "Tilters". Archived 25 July 2008 at the Wayback Machine Alternate linkAir & Space/Smithsonian, 1 September 2007. Retrieved 6 May 2015.

- Osprey Pilots Receive First FAA Powered Lift Ratings (1999 Archive from Boeing)

- Mahaffey, Jay Douglas (1991). "The V-22 tilt rotor, a comparison with existing Coast Guard aircraft" (PDF). Institutional Archive of the Naval Postgraduate School.

- "V-22 Osprey Guidebook, 2013/2014". Archived 20 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine Bell-Boeing, 2013. Retrieved 6 February 2014. Archived in 2014.

- Chavanne, Bettina H. "USMC V-22 Osprey Finds Groove In Afghanistan". [permanent dead link] Aviation Week, 12 January 2010. Retrieved 23 June 2010.

- Whittle, Richard. "Flying The Osprey Is Not Dangerous, Just Different: Veteran Pilots Archived 2012-09-14 at the Wayback Machine" defense.aol.com, 5 September 2012. Retrieved 16 September 2012. Archived on 3 October 2013.

- Adde, Nick (14 April 2021). "V-22 Upgrades in Works as Aircraft Passes Milestones". National Defense. Retrieved 22 April 2021.

- "V-22 Osprey range and ceiling" Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine. AirForceWorld.com, 6 October 2015.

- Currie, Major Tom P. Jr., USAF. "A Research Report Submitted to the Faculty, In Partial Fulfillment of the Graduation Requirements: The CV-22 'Osprey' and the Impact on Air Force Combat Search and Rescue". Archived 6 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine Air Command and Staff College, April 1999.

- "Tenacious Efforts to Accomplish Another V-22 Milestone". U.S. Navy. 17 June 2009. Archived from the original on 1 December 2016. Retrieved 19 June 2019.

- Lazarus, Aaron. DARPA-BAA 10-10, Thermal Management System (TMS) Archived 16 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine DARPA, 16 November 2009. Retrieved 18 March 2012. Quote: "MV-22 Osprey has resulted in ship flight deck buckling that has been attributed to the excessive heat impact from engine exhaust plumes. Navy studies have indicated that repeated deck buckling will likely cause deck failure before planned ship life."

- Butler, Amy (5 September 2013). "F-35B DT 2 Update: A few hours on the USS Wasp". Aviation Week & Space Technology. Archived from the original on 3 September 2014. Retrieved 4 April 2015.

- Whittle, Richard. "Fatal Crash Prompts Marines To Change Osprey Flight Rules Archived 2015-07-19 at the Wayback Machine". Breaking Defense, 16 July 2015.

- "Rolls-Royce Boosts Power for V-22 Engines". Defense News, 16 September 2013.

- US military seeking replacement V-22 engines Archived 7 September 2014 at the Wayback Machine – Flightglobal.com, 29 August 2014

- Wall, Robert, "US mulls engine options for its Osprey aircraft", The Wall Street Journal, 2 September 2014, p.B3

- "US Navy developing early plans for V-22 mid-life upgrade" Archived 16 April 2015 at the Wayback Machine – Flightglobal.com, 15 April 2015.

- John Gordon IV et al. Assessment of Navy Heavy-Lift Aircraft Options p39. RAND Corporation, 2005. Retrieved 18 March 2012. ISBN 0-8330-3791-9. Archived in 2011.

- "Hurricanes... Unleashing Nature's Fury: A Preparedness Guide". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, National Weather Service, September 2006.

- Waters, USMC Cpl. Lana D. V-22 Osprey Fast rope 1 USMC, 6 November 2004. Archived on 21 March 2005.

- Trimble, Stephen. "Boeing looks ahead to a 'V-23' Osprey". Archived 25 June 2009 at the Wayback Machine Flight Global, 22 June 2009. Archived on 12 January 2015.

- "Boeing: V-22 Osprey" (PDF). Boeing. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 November 2013. Retrieved 15 February 2014.

- Ringenbach, Daniel P. and Scott Brick. "Hardware-in-the-loop testing for development and integration of the V-22 autopilot system, pp. 28–36". Archived 28 June 2007 at the Wayback Machine Technical Papers (A95-39235 10–01): AIAA Flight Simulation Technologies Conference Technical Papers, Baltimore, MD, 3 August 2008.

- Landis, Kenneth H., et al. "Advanced flight control technology achievements at Boeing Helicopters". International Journal of Control, Volume 59, Issue 1, 1994, pp. 263–290.

- "An Afghan Report: The Osprey Returns from Afghanistan, 2012". SLD, 13 September 2012. Archived on 11 January 2015.

- Norton 2004, pp. 6–9, 95–96.

- Markman and Holder 2000, p. 58.

- Norton 2004, p. 97.

- Freedberg, Sydney J. Jr. (30 April 2021). "FVL: Don't Pick The Tiltrotor, V-22 Test Pilot Tells Army". Breaking Defense. Retrieved 3 May 2021.

- "Defensive Armament for the V-22 Selection, Integration, and Development". Bell Helicopter and General Dynamics. Retrieved: 30 December 2010.

- "BAE Systems Launches New V-22 Defensive Weapon System, Begins On-The-Move Testing". Archived 18 November 2018 at the Wayback Machine BAE Systems, 2 October 2007.

- McCullough, Amy. "Ospreys, with boost in firepower, enter Afghanistan". Marine Corps Times, 7 December 2009, p. 24.

- Whittle, Richard. "BAE Remote Guardians Join Osprey Fleet". Archived 22 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine Rotor & Wing, 1 January 2010.

- Lamothe, Dan. "Ospreys leave new belly gun in the dust". Archived 8 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine Marine Corps Times, 28 June 2010.

- "Corps seeks better weaponry on Ospreys" Archived 2 January 2014 at the Wayback Machine. Marine Corps Times, 13 February 2012.

- Corps' aviation plan calls for armed Ospreys Archived 18 December 2014 at the Wayback Machine – Marine Corps Times, 23 November 2014

- Osprey Fires Guided Rockets And Missiles In New Trials Archived 12 February 2015 at the Wayback Machine – Aviationweek.com, 8 December 2014

- V-22 demonstrates forward-firing missile capability Archived 27 December 2014 at the Wayback Machine – Flightglobal.com, 23 December 2014

- The Corps is working on an advanced reconnaissance drone that will be launched out the back of the MV-22 Osprey Archived 31 May 2019 at the Wayback Machine. Marine Corps Times. 14 May 2019.

- Boeing developing Osprey aerial refueling kit Archived 25 August 2013 at the Wayback Machine Flightglobal.com, 10 April 2013

- "Bell Boeing V-22 Osprey Deploys Refueling Equipment in Flight Test". Boeing. 5 September 2013. Archived from the original on 10 April 2015. Retrieved 4 April 2015.

- "New Pics: MV-22, Hornet in Refueling Tests" Archived 2 January 2014 at the Wayback Machine. Aviationweek.com, 3 September 2013.

- V-22 to get a tanker option Archived 29 December 2014 at the Wayback Machine – MilitaryTimes, 28 December 2014.

- US Marines set 2019 target for Osprey tanker fit Archived 7 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine – Flightglobal.com, 7 February 2017

- Whittle, Richard (27 May 2016). "V-22 Refueling Contract Highlights Close Ties To F-35". breakingdefense.com. Breaking Media, Inc. Archived from the original on 28 October 2016.

- Seck, Hope Hodge (26 October 2016). "New System Will Allow Ospreys to Refuel F-35s in Flight". dodbuzz.com. Military.com. Archived from the original on 27 October 2016.

- Navy Not Following Marines' Lead in Developing V-22 Osprey Tanker Archived 6 May 2015 at the Wayback Machine – News.USNI.org, 4 May 2015

- "Bell Boeing V-22 Osprey Fleet Surpasses 500,000 Flight Hours" (Press release). Boeing. 7 October 2019.

- "Marine Medium Tiltrotor Squadron 266 History". Archived 22 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine U.S. Marine Corps. Retrieved 16 October 2011.

- Carter, Chelsea J. "Miramar Base to Get Osprey Squadrons". Archived 17 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine USA Today (Associated Press), 18 March 2008.

- Venerable 'Sea Knight' Makes Goodbye Flights Archived 21 December 2014 at the Wayback Machine – Military.com, 3 October 2014

- Mount, Mike. "Marines to deploy tilt-rotor aircraft to Iraq". Archived 31 May 2007 at the Wayback Machine CNN, 14 April 2007.

- "Controversial Osprey aircraft heading to Iraq; Marines bullish on hybrid helicopter-plane despite past accidents". MSNBC, 13 April 2007.

- Mount, Mike. "Maligned aircraft finds redemption in Iraq, military says". Archived 10 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine CNN, 8 February 2008.

- Hambling, David. "Osprey's 'Excellent Photo Op'". Archived 5 August 2008 at the Wayback Machine Wired (CondéNet, Inc.), 31 July 2008.

- Warwick, Graham. "US Marine Corps says V-22 Osprey performing well in Iraq". Archived 9 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine Flightglobal, 7 February 2008.

- Hoyle, Craig. "USMC eyes Afghan challenge for V-22 Osprey". Archived 7 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine Flight International, 22 July 2008.

- "Department of Defense Bloggers Roundtable with Lieutenant General George Trautman, Deputy Commandant of the Marines for Aviation via teleconference from Iraq". U.S. Department of Defense, 6 May 2009. Archived 21 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine.

- Gertler, Jeremiah. (quoting USMC Karsten Heckl) "V-22 Osprey Tilt-Rotor Aircraft: Background and Issues for Congress" Archived 5 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine, p. 30. Congressional Research Service reports, 22 December 2009.

- "GAO-09-482: Defense Acquisitions, Assessments Needed to Address V-22 Aircraft Operational and Cost Concerns to Define Future Investments" (summary). Archived 24 June 2009 at the Wayback Machine Government Accountability Office. Retrieved: 30 December 2010.

- "GAO-09-482: Defense Acquisitions, Assessments Needed to Address V-22 Aircraft Operational and Cost Concerns to Define Future Investments" (full report)". Archived 24 June 2009 at the Wayback Machine U.S. Government Accountability Office, 11 May 2009.

- McLeary, Paul. "Trial By Fire". [permanent dead link] Aviation Week, 15 March 2010.

- Schanz, Marc V. "V-22s Got Dirty in Anbar". Archived 16 June 2012 at the Wayback Machine Air Force magazine, Daily Report, 25 February 2009.

- "MV-22 Logs 100,000 Flight Hours". Archived 21 February 2011 at the Wayback Machine DefenseTech, February 2011.

- Casevac, the new Osprey mission in Afghanistan Archived 5 June 2014 at the Wayback Machine – Marine Corps Times, 17 May 2014

- Talton, Trista. "24th MEU joining Haiti relief effort". Archived 18 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine Marine Corps Times, 20 January 2010. Retrieved 21 January 2010.

- Mulrine, Anna. "How an MV-22 Osprey rescued a downed US pilot in Libya". Archived 25 March 2011 at the Wayback Machine Christian Science Monitor, 22 March 2011.

- Lamothe, Dan. "Reports: Marines rescue downed pilot in Libya"[permanent dead link]. Navy Times, 22 March 2011.

- Ki Mae Heussner (2 May 2011). "USS Carl Vinson: Osama Bin Laden's Burial at Sea". Technology. ABC News. Archived from the original on 4 May 2011.; Jim Garamone (2 May 2011). "Bin Laden Buried at Sea". NNS110502-22. American Forces Press Service. Archived from the original on 23 May 2012..

- Revelos, Andrew. "HMX-1's 'Super Stallions' reassigned to operating forces". Archived 23 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine USMC, 15 April 2011.

- Munoz, Carlo. "Osprey to take on White House transport mission in 2013". Archived 29 May 2012 at the Wayback Machine The Hill, 24 May 2012.

- Reed, John. "Boeing to make new multiyear Osprey offer". Archived 22 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine Marine Corps Times, 5 May 2010. Retrieved 6 May 2010.

- Two MV-22B Osprey tiltrotor aircraft completed longest distance flight in the Pacific region Archived 31 August 2013 at the Wayback Machine – Airrecognition.com, 8 August 2013

- "Marines, Army form quick-strike forces for Africa". USA Today. 15 June 2013.

- "Marines want new technology for post-Benghazi crisis-response missions Archived 2014-04-13 at the Wayback Machine" Accessed: 9 April 2014.

- Hoyle, Craig. Archived 25 November 2013 at the Wayback Machine Flight International, 20 November 2013.

- Assistant commandant: MV-22 key to Marines' Philippines mission Archived 13 November 2013 at the Wayback Machine – MilitaryTimes, 13 November 2013

- "CV-22 delivered to Air Force". Archived 12 December 2012 at archive.today Air Force Special Operations Command News Service via Air Force Link (United States Air Force), 21 March 2006. Retrieved 3 August 2008.

- "CV-22 arrival". Archived 24 November 2007 at the Wayback Machine Hulbert Field, United States Air Force, 20 April 2006. Retrieved 20 November 2006.

- Sirak, Michael. "Osprey Ready for Combat". Archived 25 May 2009 at the Wayback Machine Air Force Magazine, Volume 92, Issue 5, May 2009, pp. 11–12. Retrieved 10 May 2009.

- Gordon, Michael R. "Attack on U.S. Aircraft Foils Evacuation in South Sudan Archived 2018-08-16 at the Wayback Machine" The New York Times, 21 December 2013.

- "Four U.S. soldiers injured in South Sudan after their aircraft CV-22 Osprey came under fire" Archived 24 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Armyrecognition.com, 22 December 2013.

- "CV-22 crews save lives" Archived 12 August 2014 at the Wayback Machine. Globalavaiationreport.com, 4 August 2014.

- "AFSOC Crash Report Faults Understanding Of Osprey Rotor Wake". Archived 23 September 2012 at the Wayback Machine AOL Defense, 30 August 2012.

- Air Force looking at using Ospreys for search and rescue – MilitaryTimes, 22 April 2015

- Tilghman, Andrew. "Tilt-rotor helicopter still looking for mission". Navy Times, 20 September 2009.

- Thompson, Loren B. "'V' For Versatility: Osprey Reaches For New Missions". Archived 10 April 2010 at the Wayback Machine Lexington Institute, 29 March 2010.

- The Future COD Aircraft Contenders: The Bell Boeing V-22 Archived 6 August 2013 at the Wayback Machine – Defensemedianetwork.com, 2 August 2013

- Israel could double V-22 order size, Bell says Archived 15 March 2014 at the Wayback Machine – Flightglobal.com, 25 February 2014

- Navy 2016 Budget Funds V-22 COD Buy, Carrier Refuel Archived 10 May 2015 at the Wayback Machine – Breakingdefense.com, 2 February 2015

- Navy and Marines Sign MOU for Bell-Boeing Osprey to be Next Carrier Delivery Aircraft Archived 18 January 2015 at the Wayback Machine – News.USNI.org, 13 January 2015

- "NAVAIR Details Changes in Navy V-22 Osprey Variant". Archived 3 April 2015 at the Wayback Machine News.USNI.org, 2 April 2015.

- Bell-Boeing begin designing CMV-22B with $151 million contract Archived 16 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine – Flightglobal.com, 1 April 2016

- Bell-Boeing begins designing CMV-22B with $151 million contract Archived 7 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine – Flightglobal.com, 1 April 2016

- U.S. Navy Orders Long-Lead Components for 6 CMV-22B Osprey From Bell Boeing Archived 11 July 2017 at the Wayback Machine – Navyrecognition.com, 29 December 2016

- US Navy reveals CMV-22B as long-range Osprey designation Archived 9 February 2016 at the Wayback Machine – Flightglobal.com, 4 February 2016.

- Navy's Osprey Will Be Called CMV-22B; Procurement To Begin In FY 2018 Archived 7 February 2016 at the Wayback Machine – News.USNI.org, 5 February 2016.

- Navy Buys First V-22 CODs as Part of $4.2B Award to Bell-Boeing Archived 4 July 2018 at the Wayback Machine. USNI News. 2 July 2018.

- "Bell Boeing Host First Reveal Ceremony for CMV-22B Osprey". Press Release. News.bellflight.com. 7 February 2020. Retrieved 9 February 2020.

- "Navy's V-22 Achieves Initial Operational Capability Designation". United States Navy.

- "Defense Ministry studies Osprey use by Self-Defense Forces". AJW by The Asahi Shimbun. Archived from the original on 9 May 2015. Retrieved 6 April 2015.

- Japan Officially Selects Osprey, Global Hawk, E-2D – Defensenews.com, 21 November 2014

- Cenciotti, David (26 August 2017). "Here Is Japan's First V-22: The First Osprey Tilt-Rotor Aircraft For A Military Outside Of The U.S." The Aviationist. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 14 October 2017.

- https://www.upi.com/Defense-News/2020/05/11/Japan-receives-its-first-V-22-Osprey-tiltrotor-aircraft/2541589214206/

- Takahashi, Kosuke (24 September 2018). "Tokyo to delay deployment of Osprey tiltrotors amid local opposition". IHS Jane's 360. Tokyo. Archived from the original on 24 September 2018. Retrieved 25 September 2018.

- Adamczyk, Ed (11 May 2020). "Japan receives its first V-22 Osprey tiltrotor aircraft". United Press International. Retrieved 23 July 2020.

- "India; ARC mulls OV-22 Osprey buy". Archived from the original on 18 May 2015. Retrieved 12 January 2019.

- "India Outlines New Carrier Ambitions". Aviation International News. Archived from the original on 16 January 2014. Retrieved 31 October 2015.

- "India sizes up V-22 Osprey". FlightGlobal. 18 January 2012. Archived from the original on 18 August 2016.

- "Bell Boeing to brief India on V-22 Osprey". stratpost.com. 5 December 2011. Archived from the original on 19 August 2016.

- "Indonesia – MV-22 Block C Osprey Aircraft". Defense Security Cooperation Agency. Archived from the original on 10 July 2020. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- "Hagel, Yaalon Finalize New Israel Military Capabilities" Archived 29 April 2013 at the Wayback Machine. U.S. DoD, 22 April 2013.

- Yuval Azulai. "Lockheed, Boeing vie for Israeli helicopter deal" Archived 25 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Globes, 24 November 2016.

- Egozi, Arie Israel steps back from V-22 purchase Archived 18 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine. Flight Global, 13 October 2017.

- Norton 2004, p. 54.

- "CV-22 Osprey Fact Sheet". Archived 23 August 2013 at the Wayback Machine United States Air Force, 7 July 2006. Retrieved 21 August 2013.

- Norton 2004, pp. 71–72.

- ""Bell-Boeing V-22 Guidebook – Bell Helicopter"" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 October 2014.

- Norton 2004, pp. 100–01.

- Norton 2004, p. 77.

- "US Marine Corps retires CH-53D" Archived 2 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Rotorhub, 24 February 2012.

- Richard Beedall (9 October 2012). "Maritime Airborne Surveillance and Control (MASC)". NNS121008-13. Naval Matters. Archived from the original on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 9 October 2011.

- Norton 2004, pp. 26–28, 48, 83–84.

- "V-22 Osprey Guidebook". Archived 11 August 2012 at the Wayback Machine Naval Air Systems Command, United States Navy, 2011/2012, p. 5.

- Norton 2004, pp. 28–30, 35, 48.

- "Japan becomes first V-22 export customer". FlightGlobal. Archived from the original on 15 July 2015. Retrieved 14 July 2015.

- World Air Forces 2014, FlightGlobal, January 2014.

- "352nd Special Operations Group". afsoc.af.mil. Archived from the original on 10 December 2008. Retrieved 7 January 2014.

- "Fact Sheet: 8 Special Operations Squadron" Archived 25 February 2013 at the Wayback Machine. U.S. Air Force, 8 August 2008.

- "CV-22 commencement of operations ceremony held" Archived 4 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine. U.S. Air Force, 21 June 2010.

- "Air Force Special Operations Command stands up CV-22 squadron in Japan". U.S. Air Force, 1 July 2019.

- "Fact Sheet: 71 Special Operations Squadron". U.S. Air Force, 3 January 2012.

- "418th FLTS tests CV-22 terrain-following radar in East Coast fog". af.mil. Archived from the original on 11 January 2015. Retrieved 6 April 2015.

- "USMC presidential helicopter squadron starts flying MV-22". 3 May 2013. Archived from the original on 21 August 2016. Retrieved 5 August 2016.

- "VMX-22 Argonauts". tripod.com. Archived from the original on 5 November 2013. Retrieved 5 November 2013.

- "VMM-161". tripod.com. Archived from the original on 12 January 2015. Retrieved 5 November 2013.

- "VMM-165". tripod.com. Archived from the original on 5 November 2013. Retrieved 5 November 2013.

- "VMM-163". tripod.com. Archived from the original on 30 March 2015. Retrieved 5 November 2013.

- "VMM-165". tripod.com. Archived from the original on 5 November 2013. Retrieved 5 November 2013.

- "VMM-166". tripod.com. Archived from the original on 5 November 2013. Retrieved 5 November 2013.

- "VMMT-204". tripod.com. Archived from the original on 5 November 2013. Retrieved 5 November 2013.

- "VMM-261". tripod.com. Archived from the original on 5 November 2013. Retrieved 5 November 2013.

- "VMM-263". usmc.mil. Archived from the original on 5 November 2013. Retrieved 5 November 2013.

- "VMM-264". tripod.com. Archived from the original on 5 November 2013. Retrieved 5 November 2013.

- "VMM-266". tripod.com. Archived from the original on 5 November 2013. Retrieved 5 November 2013.

- "VMM-362". 17 August 2018. Archived from the original on 1 September 2018. Retrieved 31 August 2018.

- "VMM-363". helis.com. Archived from the original on 5 November 2013. Retrieved 5 November 2013.

- "VMM-365". tripod.com. Archived from the original on 5 November 2013. Retrieved 5 November 2013.

- "VMM-561". tripod.com. Archived from the original on 5 November 2013. Retrieved 5 November 2013.

- "Navy.mil - View Image". Archived from the original on 10 February 2020. Retrieved 10 February 2020.

- Fuentes, Gidget (2 August 2021). "First F-35C Fighters, CMV-22B Deploy with Carl Vinson Carrier Strike Group". USNI News. Retrieved 2 August 2021.

- "Bell Boeing MV-22 Osprey accidents and incidents" Archived 15 July 2018 at the Wayback Machine Aviation Safety Network Database

- "Four dead after US military plane crashes in Norway" BBC World News 2022-03-19

- Axe, David. "General: 'My Career Was Done' When I Criticized Flawed Warplane". Archived 17 December 2018 at the Wayback Machine Wired, 4 October 2012.